What better way to celebrate Christmas than with this heartwarming discussion about reindeers that I'm sure is being replicated in homes all over the world around now between curious children and their loving guardians, assuming, of course, that their loving guardians also happen to be drunken, amoral sons-of-bitches masquerading as shopping mall Santas, which I'm entirely confident most of them are.

Or we could just keep it old school. I am, sadly, old school enough to have seen Beat Street when it came out in 1984, along with that year's other rap-sploitation hit, Breakdance. For the first time we experienced what other generations before us had, that universal white boy infatuation with (American) black street culture. As with jazz and blues before it, rap and its cultural debris, graffiti and breakdancing, hit us hard. What a sight we must have been, gawky Irish boys trying to bust our moves on flattened out pieces of cardboard in our parents' driveways or spray-painting our names under bridges before heading home because it was getting dark. Watching it now though, it's easy to hear the political message we missed then, about what Christmas is really like for those unlucky enough to find themselves on the wrong side of the economic tracks. Happy Christmas y'all. Kiss my mistletoe!

Thursday, December 23, 2010

Tuesday, December 21, 2010

The Film Club Reviews #8

I'd like to think that the stunned silence that greeted the ending of Yorgos Lanthimos' Dogtooth wasn't just shock at its unpredictable violence and sex scenes but also that people were struggling to respond to a troublingly original film, one determined to confound expectations. This seemingly surreal story about a couple who keep their grown-up children isolated from the world in a walled compound on the outskirts of a city, has the unarguable clarity of a parable and the matter-of-fact courage of its low-budget convictions. It's about repression, social and family conditioning, language, trust, corruption, sex, violence and ultimately rebellion. It's a tribute to its marvellous deadpan that it could easily be used to argue opposing positions; that the parents are repressive monsters or that the introduction of outsiders into the controlled environment disrupts the previously blissful existence of the 'children'. Or possibly both. The one thing that's unarguable is the film's belief in the maleability of human mind, that without any frame of reference we are capable of believing anything, as easily conditioned and trained as dogs. However, throughout the film there are moments when emotional outbursts, sexual desires and natural curiosity find ways to express themselves. Not let out in normal ways, they find different, less socially acceptable ways to escape. It's nature vrs nurture as some kind of social experiment then, hinting at the contradictions and failures of Communist regimes or the repressiveness of closed religious communities. In this sense it has a lot in common with Haneke's The White Ribbon. But it's a very different film, funnier, stranger, a twenty-first century Bunuelian fable, as sharp and enigmatic as a razor blade, as hard to get rid of as a stubborn tooth.

Monday, December 13, 2010

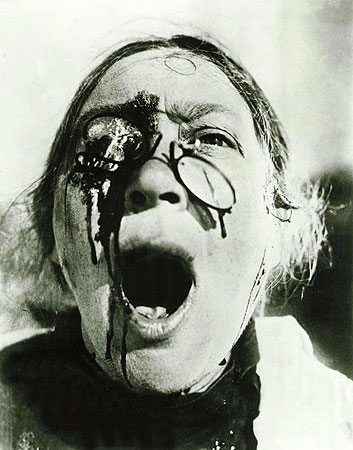

Silent Music

In the last few years I've had the pleasure of watching classic silent movies on the big screen, usually with live musical accompaniment by post-rock Irish group 3epkano. I've seen The Passion of Joan of Arc, Pandora's Box, The Blood of a Poet, Sunrise, Battleship Potemkin and The Man With the Movie Camera. I always find the combination enthralling. It's easy to sense the hold the medium had on pre-sound audiences, somehow you're more attentive to the images, faces especially, radiant in the celluloid light in ways so far removed from modern cinema it feels like a different art form, closer to alchemy than the seamless science of digital technology. I've usually come away from these screenings elated, with the faces of Maria Falconetti, Louise Brooks or Janet Gaynor seared into my mind, indelible images, religious in their iconic power.

And the music is a vital componant to this. 3epkano's great strength is there understanding of film. A friend of mine saw Lambchop doing a live score to Sunrise and said it was a disaster because they essentially played their songs over the film with little reference to it. 3epkano never do this. At times they're completely silent, letting the significance of a scene work on the images alone, sometimes they fill the silence with just the barest brush of a cymbal, moody scrape of violin, waiting for the right moment, following the narrative rhythm of the film, before building to emotional crescendos. At its best, the combination is near overwhelming, the drum beats reverberating in your chest, the violins and guitars displacing the air, sonically entering your pores. It's something else, exciting. You feel like you understand what it was like when cinema was still new, still numinous with mystery, still giddy and awe-struck by its own power. Unfortunately, no-one has yet combined 3epkano's music with images of these films on Youtube but below is one of their pieces, Everybody Is Already Down Below from their album At Land.

Tuesday, December 7, 2010

Classic Scene #25

'Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.'

- from The Dead by James Joyce

Classic Scene #24

Sometimes, though, innocence is just that, not lost just pristine like the first fall of snow, the very first time children see it, when it's not a metaphor for anything, just pure wonder and fun, like Bambi's surprise at his own footprints in the snow or Thumper's infectious excitement at discovering the water is stiff and wonderfully slippy.

Monday, December 6, 2010

Classic Scene #23

As it's started snowing heavily again outside I suppose it's time for some more snow-related movie scenes. The most famous, of course, is little Charlie Kane and that sleigh in Citizen Kane, not to mention the snowflakes skittering through time in the smashed snow globe as old Charles breathes his last. Welles returned to snow as an emblem of lost innocence again the following year in this lovely scene from The Magnificent Ambersons. But in Jim Jarmusch's blank-generation hipster classic Stranger Than Paradise , snow becomes a white-out metaphor for the empty nothing of the characters' lives as they stare out at what's supposed to be Lake Erie, but is really the bleak reality of their future lives. Surely one of the worst tourist visits ever.

You Call This Snow? Why, Back In My Day...

As a little follow-up to the Phantom Ride piece below, I thought it would be nice what with all the snow round these parts at the moment to post this, another one of those excellent BTF shorts, this time from the big freeze of 1963, its editing reminiscent at times of the giddy ecstasies of Dziga Vertov's 1929 classic The Man With The Movie Camera.

Labels:

BTF,

Dziga Vertov,

snow,

The Man With The Movie Camera

Friday, December 3, 2010

The Phantom Ride

Before there was cinema, there was the train. It might seem fanciful but I'd like to make the claim that train travel not only prepared people for the idea of cinema but may even have been a catalyst for its eventual creation. Invention is such a mystery, after all, something in the air of the times, a whisper of influences waiting to coalesce. Surely the idea that still images could move was born in the mind of someone sitting by a train window watching the world go by, or millions of people sitting by thousands of train windows watching endless fields and suburbs go by. It was in the air. Cinema the idea was already an invention of the imagination long before science and technology caught up. This was the era of camera obscura towers, magic lantern shows and experiments in capturing the secrets of motion by men like Eadweard Muybridge and Jules Maray. Cinema was the culmination of all these processes, all these primitive yearning mechanisms for capturing life.

The wonder of early cinema wasn't in stories or acting or montage it was just this; the mystery of suspended time, of captured motion. Just like train travel. Who, after all, hasn't been lulled into a time-forgetting dream-state by the clickity-clack rhythms of a train, the rolling cinema of carriage windows? The analogy was there from the start. They were kindred spirits, both symbols of progress, both promising journeys to other places, both foreshortening distance and time in ways society had never imagined before.

And so, naturally, it was to the train that the earliest filmmakers were drawn again and again, in homage and unconscious recognition. Between those famous train-centred milestones of early cinema, the Lumiere Bros panic-inducing L'Arrivée d'un train à La Ciotat (1896) and Edwin S. Porter's narrative breakthrough The Great Train Robbery (1903) lies a generally less well-known period of sensation, novelty and gradual evolution, when techniques were discovered that are still with us today. And one of the most popular and profound of these was the phantom ride, an evolutionary step forward for the fledgling medium, one in which it stopped simply recording motion and instead became motion itself.

In the typically cavalier fashion of the times the effect was achieved by tying a cameraman to the buffer of a moving train and having him crank away as it sped along the track. The means may have been primitive, not to mention dangerous, but the result was a sensation, a ghostly ride through the air, as if the viewer were floating above the track, a disembodied dream eye travelling into the darkness of tunnels and towards the light on the other side. Audiences couldn't get enough of these virtual thrill rides which were often, appropriately enough, shown at travelling fairgrounds as part of a programme of similarly short actualities, comedies and trick-films. The earliest known example, Biograph's The Haverstraw Tunnel (1897), was an instant hit, spawning dozens of imitators including Railway Trip Over The Tay Bridge (1897), View From An Engine Front - Ilfracombe (1898) and View From an Engine Front - Train Leaving Tunnel (1899). The latter was used by one of the most innovative filmmakers of the time, G.A. Smith, to create his influential A Kiss In The Tunnel (1899). It consists of only three shots; train enters tunnel, man kisses woman in the dark compartment, train exits tunnel. It might not sound like much now but this was a major advance in editing and continuity leading the medium towards more sophisticated story-telling.

Although single-shot phantom rides continued after this, well into the new century, taking in ever more exotic and far-flung places from the front of ships and trams as well as subway trains, it was soon just another technique in an ever-expanding arsenal of possibilities. The success of The Great Train Robbery had marked the end of simple awe and curiosity and the start of cinema as a serious art form with all the potential range of novels and theatre.

But there was to be one final hurrah for the pure phantom ride form, one which brought the relationship between trains and films to its logical conclusion. In 1905 a Kansas City Fire Chief named George C. Hale created a nickelodeon amusement called Hale's Tours and Scenes of the World. This 'illusion ride' consisted of mock train carriages showing ten-minute films of scenes from around the world. But they weren't just novelty cinemas. While the passengers watched these phantom ride films, projected onto the end of the carriage to create the illusion of actually travelling through these scenes, like they were looking through a window, the carriage would simulate the motion of a real train, rocking and swaying from side to side while steam and train whistle sound effects played and painted scenery rolled past the windows.

The Hale's Tour had finally made real what had always been implied; that being in a train and watching a film were essentially the same thing, that illusion and travel worked on the imagination in much the same way, creating intermediary zones away from the real world where people could dream and forget. Not surprisingly, they proved insanely popular. By 1907 there were five hundred all over the United States, and many more around the world in places like Melbourne, Paris, Hong Kong and London, which had no less than four, with others in Manchester, Blackpool, Leeds and Bristol.

Despite this success, the truth was the phantom ride had effectively been shunted onto a siding of cinema history, merely a passing fad, a necessary but primitive first step in the maturity of a great new art form. And watching the surviving examples today it's easy to dismiss these grainy, ponderously slow artifacts, to wonder how they could ever have had such an electrifying effect on audiences. But speed is relative and what would have given a Victorian a nosebleed barely feels like moving now. In 1962 a British Transport documentary called Let's Go To Birmingham revived the form to record the journey from London's Paddington Station to Birmingham's Snow Hill but with one crucial difference, they speeded it up so the entire journey takes only five minutes. It's still a blast and is probably a modern viewer's best chance at understanding what it was like to see the first phantom rides.

Today the phantom ride has become a standard cinematic device for putting audiences into the heart of the action, little different at times to its thrill ride origins (note its use in the current 3D craze, like the rollercoaster scene in Despicable Me for example). But it's also been used for the opening title sequences of films like Get Carter (1971), The Warriors (1979) and David Lynch's Lost Highway (1996), not just as a way to create an immediate sense of momentum and excitement but also to put us in the right frame of mind for the film to come, to lure us into the disembodied dream-state of film itself. One phantom ride, you could say, preparing us for another.

The Phantom Ride originally appeared in online arts magazine Oomska

Wednesday, December 1, 2010

Crime City USA

I first came across RubyTuesday717 when I chanced upon her The Endless Night: A Valentine to Film Noir, a fan video so good it made me want to hijack an old cinema and watch nothing but film noirs day and night until that double-crossing blonde betrayed me to the cops and I died in a hail of bullets trying to shoot my way out. I didn't, of course, but I did watch The Endless Night over and over again. It was that good. Later I used her tribute to Notorious as the perfect ending to a piece I wrote about that fantastic film.

And now she's done it again, produced another absorbing tribute, this time to all the 'delicious, sinful crime films' set in San Francisco, piecing together images and moments from Dark Passage, The Maltese Falcon, Zodiac, Dirty Harry, Vertigo and Bullitt to name just a few, and adding inspired music, mainly Donovan's Hurdy Gurdy Man, with other snippets from Henry Mancini, Smashing Pumpkins and John Murphy. The result is not only exciting and ingenious, an admirable work in of itself, but it also invokes a love for its subject matter so intense it makes you want to watch all of these films, all at once, in a hijacked old cinema, of course, with a duplicitous blonde by your side, whispering sweet oblivion in the dark.

Monday, November 22, 2010

Classic Scene #22

Nic Roeg's Don't Look Now is a ghost story with a difference, built on the usual Gothic principles of premonition and dread but complicated by more emotionally profound kinds, the unspoken fears lurking in every parental mind, the potential for loss, the devastation of grief and guilt. The result is like nothing you've ever seen. Roeg's unique style, a quantum splintering of time, poetic connections between images, motifs chiming and cameras zooming with woozy significance, all come together in this opening scene to create a technically sublime waking nightmare, horror movie rhyming with muddy reality, every superstitious fear rooted in real fear, verified by it, the unthinkable making everything possible, necessary even.

Friday, October 29, 2010

Classic Scene #21

On a more genuinely scary note, here's another medium getting in contact with the dead, but we're a long way from dotty old Madame Acarti here. In this scene from superb Spanish chiller The Orphanage a paranormal investigation team led by the psychic Aurora (Geraldine Chaplin) attempt to make contact with the spirits of the old orphanage. There are no laughs in this one.

Classic Scene #20

To get everyone into the Halloween mood, a little seance with Madame Acarti. Mind you, Blithe Spirit being a Noel Coward play it's a very British kind of seance, played mainly for laughs. But atmospheric direction courtesy of David Lean and the wonderfully bonkers Margaret Rutherford as Madame Acarti eerily channeling a little girl's voice make it more than just a comic scene.

Tuesday, October 26, 2010

Last Five Films...#4

1. Dawn of the Dead (1979)

Shown in conjunction with A History of Horror, Mark Gatiss' excellent three-part series for BBC4, Dawn of the Dead is a classic despite its manifest flaws. The analogy I've come up with to explain this is the difference between Frank Sinatra's Songs For Swinging Lovers and Ramones by The Ramones. The first is the result of supremely talented people on the top of their game, Sinatra's voice and phrasing, Nelson Riddle's arrangements, the finest session musicians money could buy, not to mention The Great American Songbook of Cole Porter and George Gershwin. It's so evidently a high watermark of moden culture it doesn't need any special pleading.

The Ramones, on the other hand, the original three-cord punks, weren't even the best musicians in scummy New York dive CBGBs in 1975 (Television or Talking Heads if you're asking) and had only one basic idea, gonzo, speed-freak versions of 50s pop. But what an idea it was, especially when attacked with dumb-ass gusto on classics like Blitzkrieg Pop and Beat On The Brat.

The point is, taste and talent would never have given us this. Likewise, they would never have given us Dawn of the Dead. It took an instinctive amateur to go there. Romero's direction is borderline incompetent at times, especially with action sequences, and the actors are often all at sea, but there's no denying the moral intelligence behind it or the now-iconic images of zombies wandering through the shopping mall as cheery Muzak plays, filmmaking so savagely satirical and sweetly funny that no-one except maybe the Kubrick of Dr Strangelove would have dared go there.

2. The Quatermass Experiment (1955)

The Quatermass Experiment is a very effective early Hammer sci-fi/horror about a rocket ship returning to earth infected by a mysterious alien organism. Excellent location shooting and a haunting performance by Richard Wordsworth (as the only surviving astronaut slowly being taken over by this thing inside him), give this spin-off from a landmark TV series real bite. As maverick scientist Dr Quatermass, veteran American actor Brian Donlevy waltzes around 50s Britain like he owns it, ignoring or browbeating everyone from the military and the police to medical experts as if none of the rules apply to him (which may have been some kind of sly political statement of course).

3. Despicable Me (2010)

Another week another entertaining animated film. If only my kids realised what a golden age of childrens' cinema they're living through. Even sequel-fodder like Ice Age 3 offers more invention and wit than most adult films. In fact it's easy to take the visual flair and comic timing of a film like Despicable Me for granted. It may not be the latest ground-breaking animation from Pixar, criminal mastermind Gru may be a cross between Uncle Fester and Dr Evil, the plot a variation on The Grinch and the visual style half-inched from Henry Selick, but it doesn't matter. My kids loved it, the minions are funny and it manages the inevitable heartwarming ending with enough delicate skill to avoid mawkishness.

4. Army of Shadows (1969)

Superbly laconic account of the French Resistance showing how ordinary people became as ruthless as the enemy and as devious as criminals to survive the Occupation. There's an air of existential gloom over it all, from the closed, watchful faces, the dour overcast skies, the lonely sound of hard shoes on cobbled streets, the cowed eyes of men who know they're going to be killed. It's difficult to sympathise with anyone though, because the sense of honour and sacrifice is alien to us now, the idea of killing your own because they've betrayed you. It's hard to justify when they're just kids who made mistakes or women trying to protect their children. The film is unflinching in this and while the middle section in wartime London is a little unconvincing overall it's a compelling work.

5. Fool's Gold (2008)

I have a soft-spot for Matthew McConaughey (no not quicksand). I honestly think he could've been this generation's Errol Flynn if the roles had come his way. Only the enjoyable Sahara gave him a proper opportunity to show what a likeable wise-cracking hero he could be. Too often he's been tied down to lame rom-com plots opposite B-list actresses and Fool's Gold is no help; a half-baked treasure hunt plot shackled to contrived romantic fireworks opposite charisma-free Kate Hudson. Despite a few bright moments it doesn't work. And I really wanted to like it, I really did. But it just gets progressively worse as first Donald Sutherland and then Ray Winstone compete to see who can produce the worst accent in cinema history. Winstone wins by a nautical mile, his Southern-drawl-meets-East-London-snarl so toe-curlingly bad McConaughey should have taken it as a personal insult and challenged him to pistols at dawn and saved us all this witless waste of time.

Shown in conjunction with A History of Horror, Mark Gatiss' excellent three-part series for BBC4, Dawn of the Dead is a classic despite its manifest flaws. The analogy I've come up with to explain this is the difference between Frank Sinatra's Songs For Swinging Lovers and Ramones by The Ramones. The first is the result of supremely talented people on the top of their game, Sinatra's voice and phrasing, Nelson Riddle's arrangements, the finest session musicians money could buy, not to mention The Great American Songbook of Cole Porter and George Gershwin. It's so evidently a high watermark of moden culture it doesn't need any special pleading.

The Ramones, on the other hand, the original three-cord punks, weren't even the best musicians in scummy New York dive CBGBs in 1975 (Television or Talking Heads if you're asking) and had only one basic idea, gonzo, speed-freak versions of 50s pop. But what an idea it was, especially when attacked with dumb-ass gusto on classics like Blitzkrieg Pop and Beat On The Brat.

The point is, taste and talent would never have given us this. Likewise, they would never have given us Dawn of the Dead. It took an instinctive amateur to go there. Romero's direction is borderline incompetent at times, especially with action sequences, and the actors are often all at sea, but there's no denying the moral intelligence behind it or the now-iconic images of zombies wandering through the shopping mall as cheery Muzak plays, filmmaking so savagely satirical and sweetly funny that no-one except maybe the Kubrick of Dr Strangelove would have dared go there.

2. The Quatermass Experiment (1955)

The Quatermass Experiment is a very effective early Hammer sci-fi/horror about a rocket ship returning to earth infected by a mysterious alien organism. Excellent location shooting and a haunting performance by Richard Wordsworth (as the only surviving astronaut slowly being taken over by this thing inside him), give this spin-off from a landmark TV series real bite. As maverick scientist Dr Quatermass, veteran American actor Brian Donlevy waltzes around 50s Britain like he owns it, ignoring or browbeating everyone from the military and the police to medical experts as if none of the rules apply to him (which may have been some kind of sly political statement of course).

3. Despicable Me (2010)

Another week another entertaining animated film. If only my kids realised what a golden age of childrens' cinema they're living through. Even sequel-fodder like Ice Age 3 offers more invention and wit than most adult films. In fact it's easy to take the visual flair and comic timing of a film like Despicable Me for granted. It may not be the latest ground-breaking animation from Pixar, criminal mastermind Gru may be a cross between Uncle Fester and Dr Evil, the plot a variation on The Grinch and the visual style half-inched from Henry Selick, but it doesn't matter. My kids loved it, the minions are funny and it manages the inevitable heartwarming ending with enough delicate skill to avoid mawkishness.

4. Army of Shadows (1969)

Superbly laconic account of the French Resistance showing how ordinary people became as ruthless as the enemy and as devious as criminals to survive the Occupation. There's an air of existential gloom over it all, from the closed, watchful faces, the dour overcast skies, the lonely sound of hard shoes on cobbled streets, the cowed eyes of men who know they're going to be killed. It's difficult to sympathise with anyone though, because the sense of honour and sacrifice is alien to us now, the idea of killing your own because they've betrayed you. It's hard to justify when they're just kids who made mistakes or women trying to protect their children. The film is unflinching in this and while the middle section in wartime London is a little unconvincing overall it's a compelling work.

5. Fool's Gold (2008)

I have a soft-spot for Matthew McConaughey (no not quicksand). I honestly think he could've been this generation's Errol Flynn if the roles had come his way. Only the enjoyable Sahara gave him a proper opportunity to show what a likeable wise-cracking hero he could be. Too often he's been tied down to lame rom-com plots opposite B-list actresses and Fool's Gold is no help; a half-baked treasure hunt plot shackled to contrived romantic fireworks opposite charisma-free Kate Hudson. Despite a few bright moments it doesn't work. And I really wanted to like it, I really did. But it just gets progressively worse as first Donald Sutherland and then Ray Winstone compete to see who can produce the worst accent in cinema history. Winstone wins by a nautical mile, his Southern-drawl-meets-East-London-snarl so toe-curlingly bad McConaughey should have taken it as a personal insult and challenged him to pistols at dawn and saved us all this witless waste of time.

Sunday, October 10, 2010

Great Title Sequences #3

After the disastrous School Daze (1988) Spike Lee was under pressure to prove his break-out film She's Gotta Have It (1986) wasn't just a fluke. Many promising directors haven't recovered from similar missteps, self-doubt sending them in search of the temporary safety of formulaic studio work, from where they either disappear or become careerist hacks for hire.

So the title sequence to Do The Right Thing (1989), amongst other things, can be seen as a statement of intent, Lee coming out fighting, refusing to compromise, reasserting his right to be considered a true autuer and not just someone who got lucky once.

And what a statement it is, an incendiary way to start an incendiary film, a bombardment of expressionist colour, lighting and sound from the audacious camera dolley that starts it, to the in-your-face intensity of Rosie Perez's dancing, to the thrilling rap soundtrack of Public Enemy's epic Fight The Power.

Before you have any idea what this film is about you know it's about anger and heat and sex and the sensery overload of city life and a director saying, in no uncertain terms, bring it on.

So the title sequence to Do The Right Thing (1989), amongst other things, can be seen as a statement of intent, Lee coming out fighting, refusing to compromise, reasserting his right to be considered a true autuer and not just someone who got lucky once.

And what a statement it is, an incendiary way to start an incendiary film, a bombardment of expressionist colour, lighting and sound from the audacious camera dolley that starts it, to the in-your-face intensity of Rosie Perez's dancing, to the thrilling rap soundtrack of Public Enemy's epic Fight The Power.

Before you have any idea what this film is about you know it's about anger and heat and sex and the sensery overload of city life and a director saying, in no uncertain terms, bring it on.

Labels:

Do The Right Thing,

great title sequences,

Spike Lee

Sunday, October 3, 2010

Classic Scene #19

Tony Curtis was one of the most recognisable movie stars in the world, but his fame was built on only a few good movies. Naming six would be a challenge. Not surprisingly then, most of the focus after his death has been on Some Like It Hot and to a lesser extent Sweet Smell Of Success (both amazing films, unquestionably his best performances, so no complaints there). Still, I'd like to pay tribute to his passing with a scene from one of the others worth mentioning, Blake Edward's The Great Race (1965), a period farce in the style of It's A Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1963) or Those Magnificent Men In Their Flying Machines (1965), reuniting Curtis with his Some Like It Hot co-star Jack Lemmon. The scene I've picked is the fantastic custard pie fight, arguably the finest in movie history. I like to imagine it's where Curtis is now, in that eternal custard pie fight in the sky with Lemmon at his daffy best and the divine Natalie Wood.

Monday, September 27, 2010

Great Title Sequences #2

I love Walter Hill's The Warriors , in no small part due to the opening credit sequence. It's a little masterclass in how you can establish location, character, plot and mood all before the film's even started. Everything about it is great: the opening shot of the Coney Island Ferris Wheel, spokes lighting up against the night sky, (all paths metaphorically leading to the centre), the fantastic theme music driving everything forward, graffiti-credits looming out of the darkness, spray-paint red coolly blending with station-light blue against the tunnel blackness, the intercutting of the dialogue scenes with the train speeding towards the city. Honestly, it's almost a pity it has to end, I could quite happily watch a whole film of this, narrative evolving in clipped statements intercut with shots of the train moodily hurtling through the night. By the time it does end, the audience, if they're anything like me, is giddy with anticipation for what's to come. As the man says, 'whole lotta magic.'

Labels:

great title sequences,

The Warriors,

Walter Hill

Saturday, September 25, 2010

The Film Club Reviews #7

The White Ribbon (2009)

The second film of our winter season was in stark contrast to the first, (feelgood Irish documentary His & Hers). As always with Haneke much is left unsaid or hinted at with mysterious events threatening the status quo of seemingly normal society, in this case, a small village in Northern Germany on the eve of the First World War. Visually and thematically recalling the Scandinavian austerity of Dreyer and Bergman (but with a devastating frankness all its own), it also exudes a mise-en-scène mastery worthy of Hitchcock. And as with Hitchcock, at heart the mystery is a McGuffin, a means to darker moral ends. Haneke isn't interested in who kidnapped the children or burned down the barn, his real concern is in what these events reveal about family life and society at large. We watch religious repression and social conformity incubate violence and intolerance, ordinary youthful vitality and exuberance denounced in the name of idealised goodness. It's not too difficult to imagine these children twenty years later, conditioned by stern authority and desire for purity, voting for a regime promising them both. With stunning black and white photography capturing every child's face in vibrant close-up, faces brimming with confusion, hurt, trust and defiance, The White Ribbon will linger long in the mind.

The second film of our winter season was in stark contrast to the first, (feelgood Irish documentary His & Hers). As always with Haneke much is left unsaid or hinted at with mysterious events threatening the status quo of seemingly normal society, in this case, a small village in Northern Germany on the eve of the First World War. Visually and thematically recalling the Scandinavian austerity of Dreyer and Bergman (but with a devastating frankness all its own), it also exudes a mise-en-scène mastery worthy of Hitchcock. And as with Hitchcock, at heart the mystery is a McGuffin, a means to darker moral ends. Haneke isn't interested in who kidnapped the children or burned down the barn, his real concern is in what these events reveal about family life and society at large. We watch religious repression and social conformity incubate violence and intolerance, ordinary youthful vitality and exuberance denounced in the name of idealised goodness. It's not too difficult to imagine these children twenty years later, conditioned by stern authority and desire for purity, voting for a regime promising them both. With stunning black and white photography capturing every child's face in vibrant close-up, faces brimming with confusion, hurt, trust and defiance, The White Ribbon will linger long in the mind.

Thursday, September 16, 2010

Great Title Sequences #1

We have to start with the grandaddy of all title sequences, the Saul Bass-designed credits for Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo. They're so good, in fact, they have us hooked even before they begin. In the darkness we hear the first strains of Bernard Herrmann's music, instantly invoking that state of heightened dreaming that is cinema. Then the Paramount logo appears, in black and white, from which a huge V looms towards us, for all the world like a plunging scissors, becoming the centre of the word VistaVision (rarely can a brand name have seemed so ominous). Already, even before the titles have started, we're enveloped in the uneasy dream-mood of the film to come. This is no accident. As Bass explained, 'my initial thoughts about what a title can do was to set mood and the prime underlying core of the film's story, to express the story in some metaphorical way. I saw the title as a way of conditioning the audience, so that when the film actually began, viewers would already have an emotional resonance with it.' So the titles proper begin. The camera roams across a woman's face, from the pallor of her cheek to her pursed lips, from both eyes nervously looking askance to a close-up of one, liquid-dark eye. Feminine allure and mystery established we enter the spiraling world of that eye. 'Design is thinking made visual,' Bass declared, and somehow this sequence seems more than just visually striking. It's metaphor and hypnosis, endlessly mysterious and suggestive. When it ends our emotional resonance is well and truly primed for what's to come.

Labels:

great title sequences,

hitchcock,

saul bass,

Vertigo

Tuesday, September 14, 2010

Classic Scenes #18

The pleasure of this scene from Harvey (1950) isn't just the quoteable wisdom of the words but also the music of their delivery. While all the focus is rightly on Stewart's iconic Elwood P. Dowd, don't miss the plummy rhythms of Cecil Kellaway as psychiatrist Dr. Chumley, the way he uses those crisp consonants and rolling rs to run his words into each other, riding the internal rhymes of lines like 'this sister of yours is at the bottom of a conspiracy against you.'

But then there's that lovely, rueful 'Ohhh doctor' from Stewart and like one musician handing over to another, he begins his solo. Notice the run-over into the next sentence before 'she always called me Elwood', those softly echoing 'oh sos' and the warm emphasise of 'I recommend pleasant'. It's a masterclass of tone and rhythm and I never grow tired of hearing or seeing it.

But then there's that lovely, rueful 'Ohhh doctor' from Stewart and like one musician handing over to another, he begins his solo. Notice the run-over into the next sentence before 'she always called me Elwood', those softly echoing 'oh sos' and the warm emphasise of 'I recommend pleasant'. It's a masterclass of tone and rhythm and I never grow tired of hearing or seeing it.

Sunday, August 29, 2010

The Archetype Abides

For psychologist Carl Jung his patients' dreams were to be taken as seriously as any waking experience they may have had. If one described a dream about traveling to India, Jung would get a map and ask him to point out exactly where in India he had been.

Taking the dream experience seriously, as an arena of symbolic clues, led him to believe that the psyche contained common archetypes, recurrent images that could be found in cultures all over the world, past or present, primitive or modern.

Studying ancient texts and traveling the world, spending time in African villages and American-Indian reservations, he came to believe people saw these images in dreams or visions, that these states were a way for our minds to access a reservoir of shared knowledge, what he variously called universal consciousness or the collective unconscious.

BRYSON: I understand that the geology confirms the images. The images are your private images in Dali's head but painted out they correspond to a reality.

DALI: Exactly...my delirium is injected and sublimate in these rocks and in this geology. There's many kinds of imagination, [such as] the Romantic imagination, almost never exist in rock. It's only fog, music, evanescent visions of Nordic countries [where] everything is completely musical. This also is very clear in my moustache because my moustache is the contrary of the moustache of Friedrich Nietzsche. Friedrich Nietzsche is the depressive moustache, plenty of music and fog and romanticism and the Dalí moustache is exactly the same que two erected scissors completely metallic.

Salvador Dalí, interview with David Bryson, BBC Third Programme, 1962

In his autobiography Dali told a story about how he used to go walking with a girl to whom he showed off with copies of L'Esprit Nouveau, a magazine edited by Le Corbusier and Fernand Leger: 'she would humbly bow her forehead in an attentive attitude over the Cubist paintings. At this period I had a passion for what I called Juan Gris' 'Categorical imperative of mysticism'. I remember often speaking to my mistress in enigmatic pronouncements, such as, 'Glory is a shiny, pointed, cutting thing, like an open pair of scissors'...'

Before the age of digital editing suites, the link between film and scissors was always strong. It was the chief implement in the editing process, that destructive act of cutting that gave birth to the language of cinema, montage. Alfred Hitchcock was a passionate believer in the manipulative power of montage, so it's no surprise he held the humble scissors in such high regard.

In his book The Hitchcock Murders, Peter Conrad tells of a Lincoln Centre tribute to Hitchcock in 1974, during which the great man watched a compilation of clips from his films. The anthology of abreviated killings concluded with Grace Kelly stabbing her attacker in Dial M for Murder. 'The best way to do it,' Hitchcock commented, 'is with scissors.'

The idea of the scissors predictably stimulated Hitchcock's taste buds. For him, murder was aesthetic, erotic, but also appetitive. He rejected a shot from Dial M for Murder because the blades of the scissors did not flash as they arched through the air. 'A murder without gleaming scissors,' he reasoned, 'is like asparagus without the Hollandaise sauce - tasteless.'

Peter Conrad, The Hitchcock Murders

When Hitchcock and Dali came together to collaborate on the dream sequence for Spellbound (1945), it's no surprise to see scissors playing such a prominent role, a giant pair slicing through eyeballs, not only in homage to Bunuel's Un Chien Andalou (1928) but also in symbolic allusion to the editing process itself, its power to do violence to our minds via our eyes. Cinema, this moment implies, is the unconscious incarnate, a shining implement to access those archetypal images buried deep in our dreams.

Fifty years later and those same giant scissors made another appearance in a dream sequence. Everyone remembers the feelgood gutterball sequence in The Big Lebowski, but possibly tend to forget how it ends, the Dude being chased by three nihilists in orange body-suits brandishing enormous, threatening scissors.

Is this an example of Jung's archetypal unconscious at work? Did one or both of the Coen's dream those scissors, or see them in a vision? Or were they found in a studio cupboard, left there ever since filming on Spellbound finished? Or is it simply that the Coens know their film history so well that they wanted to pay homage to Hitchcock's dream-image in much the same way he did to Bunuel's all those years before? You decide.

Taking the dream experience seriously, as an arena of symbolic clues, led him to believe that the psyche contained common archetypes, recurrent images that could be found in cultures all over the world, past or present, primitive or modern.

Studying ancient texts and traveling the world, spending time in African villages and American-Indian reservations, he came to believe people saw these images in dreams or visions, that these states were a way for our minds to access a reservoir of shared knowledge, what he variously called universal consciousness or the collective unconscious.

BRYSON: I understand that the geology confirms the images. The images are your private images in Dali's head but painted out they correspond to a reality.

DALI: Exactly...my delirium is injected and sublimate in these rocks and in this geology. There's many kinds of imagination, [such as] the Romantic imagination, almost never exist in rock. It's only fog, music, evanescent visions of Nordic countries [where] everything is completely musical. This also is very clear in my moustache because my moustache is the contrary of the moustache of Friedrich Nietzsche. Friedrich Nietzsche is the depressive moustache, plenty of music and fog and romanticism and the Dalí moustache is exactly the same que two erected scissors completely metallic.

Salvador Dalí, interview with David Bryson, BBC Third Programme, 1962

In his autobiography Dali told a story about how he used to go walking with a girl to whom he showed off with copies of L'Esprit Nouveau, a magazine edited by Le Corbusier and Fernand Leger: 'she would humbly bow her forehead in an attentive attitude over the Cubist paintings. At this period I had a passion for what I called Juan Gris' 'Categorical imperative of mysticism'. I remember often speaking to my mistress in enigmatic pronouncements, such as, 'Glory is a shiny, pointed, cutting thing, like an open pair of scissors'...'

Before the age of digital editing suites, the link between film and scissors was always strong. It was the chief implement in the editing process, that destructive act of cutting that gave birth to the language of cinema, montage. Alfred Hitchcock was a passionate believer in the manipulative power of montage, so it's no surprise he held the humble scissors in such high regard.

In his book The Hitchcock Murders, Peter Conrad tells of a Lincoln Centre tribute to Hitchcock in 1974, during which the great man watched a compilation of clips from his films. The anthology of abreviated killings concluded with Grace Kelly stabbing her attacker in Dial M for Murder. 'The best way to do it,' Hitchcock commented, 'is with scissors.'

The idea of the scissors predictably stimulated Hitchcock's taste buds. For him, murder was aesthetic, erotic, but also appetitive. He rejected a shot from Dial M for Murder because the blades of the scissors did not flash as they arched through the air. 'A murder without gleaming scissors,' he reasoned, 'is like asparagus without the Hollandaise sauce - tasteless.'

Peter Conrad, The Hitchcock Murders

When Hitchcock and Dali came together to collaborate on the dream sequence for Spellbound (1945), it's no surprise to see scissors playing such a prominent role, a giant pair slicing through eyeballs, not only in homage to Bunuel's Un Chien Andalou (1928) but also in symbolic allusion to the editing process itself, its power to do violence to our minds via our eyes. Cinema, this moment implies, is the unconscious incarnate, a shining implement to access those archetypal images buried deep in our dreams.

Fifty years later and those same giant scissors made another appearance in a dream sequence. Everyone remembers the feelgood gutterball sequence in The Big Lebowski, but possibly tend to forget how it ends, the Dude being chased by three nihilists in orange body-suits brandishing enormous, threatening scissors.

Is this an example of Jung's archetypal unconscious at work? Did one or both of the Coen's dream those scissors, or see them in a vision? Or were they found in a studio cupboard, left there ever since filming on Spellbound finished? Or is it simply that the Coens know their film history so well that they wanted to pay homage to Hitchcock's dream-image in much the same way he did to Bunuel's all those years before? You decide.

Labels:

dali,

hitchcock,

jung,

spellbound,

The Archetype Abides,

the big lebowski,

the coen brothers

Saturday, August 21, 2010

Here Be Monsters

Spanish painter Goya's famous dictum that 'the sleep of reason breeds monsters' has special significance for cinema, which has always been happy to show us those monsters, to use our superstitions and fears against us. What Goya was getting at was the way sleep leaves us vulnerable to the thoughts and desires we'd rather not acknowledge. So those conditions that impose sleep on us without our control are particularly frightening.

We all know stories of people who sleep-walk, of children sitting up in bed in the middle of the night, seemingly in a trance, holding conversations with siblings they have no memory of the next morning. These incidents are usually recounted as funny stories but the reality of the moment is certain to have been unsettling. We don't like not being in control in this way or even seeing it in others. It provokes too many questions we don't have answers for. What monsters are we prey to in our sleep? In what ways are they controlling us? What would we see if we remembered these states? Are dreams just surreal mental debris or coded visions of the future? Many societies have certainly associated trances with precognition.

Part of the appeal of cinema is its mimicking of this state but with the comforting knowledge that we are, more or less, in control, the monsters can't really get us. But not everyone believes this. The public outcry against video nasties in the 80s, or the knee-jerk attempt to blame certain movies for the acts of those who go on killing sprees suggests that there is an instinctive fear that invoking our hidden demons on the screen can somehow activate them in our minds, bring them into this world, as if the cinema acted as some kind of portal between our dreams and reality. At the very least it suggests that our unease with sleep has passed over to the daydream of cinema. The two are inextricably linked, versions of each other. We don't need intellectuals or critics to make the connection, we feel it instinctively.

Which is all another way of saying that the somnambulist may be the perfect cinematic subject, the sleepwalker who can see visions, who can be manipulated into participating in terrible acts under the spell of sleep. Just like us, of course, accessories in the dark.

The most famous movie somnambulist appeared as far back as 1920 in the expressionist masterpiece The Cabinet of Dr Caligari. He was Cesare, plaything of the sinister Caligari, owner of a stand in a traveling fair that visits a small German town. The townsfolk are encouraged to ask Cesare questions. One asks how long he will live and gets the reply, 'you will die tomorrow.' Which he promptly does.

The film is most famous today for its groundbreaking art direction, using theatrical set design to create a distorted world of narrow streets and angular buildings, deliberately artificial and exaggerated to represent the nightmarish world of the cursed Cesare.

Fittingly, it also predicted the future, with Caligari a premonition of another charismatic madman on the horizon and Cesare the German people, all too easily sleepwalked into atrocity.

That's the trouble with letting dreams into the world, y'see. Pretty soon you don't know what's real anymore, what's true. And as Dostoevsky made clear in The Brothers Karamazov: if nothing is true, then everything is permitted.

Eighty years later and another somnambulist is manipulated by a sinister figure to commit a series of crimes. In Richard Kelly's Donnie Darko, troubled teen Donnie's sleep-visions of a giant rabbit also give him access to the future, not the death of individuals this time but the death of everyone, the end of the world. Of course, in the film's quantum time, the possibility exists that Donnie is both dead and alive at the same time, like Schrodinger's Cat, suspended in a dream state between knowing and imagining. Either way, sleep remains a dangerous mystery, that place on old maps yet to be fully explored, where superstitious cartographers usually wrote:

here be monsters.

We all know stories of people who sleep-walk, of children sitting up in bed in the middle of the night, seemingly in a trance, holding conversations with siblings they have no memory of the next morning. These incidents are usually recounted as funny stories but the reality of the moment is certain to have been unsettling. We don't like not being in control in this way or even seeing it in others. It provokes too many questions we don't have answers for. What monsters are we prey to in our sleep? In what ways are they controlling us? What would we see if we remembered these states? Are dreams just surreal mental debris or coded visions of the future? Many societies have certainly associated trances with precognition.

Part of the appeal of cinema is its mimicking of this state but with the comforting knowledge that we are, more or less, in control, the monsters can't really get us. But not everyone believes this. The public outcry against video nasties in the 80s, or the knee-jerk attempt to blame certain movies for the acts of those who go on killing sprees suggests that there is an instinctive fear that invoking our hidden demons on the screen can somehow activate them in our minds, bring them into this world, as if the cinema acted as some kind of portal between our dreams and reality. At the very least it suggests that our unease with sleep has passed over to the daydream of cinema. The two are inextricably linked, versions of each other. We don't need intellectuals or critics to make the connection, we feel it instinctively.

Which is all another way of saying that the somnambulist may be the perfect cinematic subject, the sleepwalker who can see visions, who can be manipulated into participating in terrible acts under the spell of sleep. Just like us, of course, accessories in the dark.

The most famous movie somnambulist appeared as far back as 1920 in the expressionist masterpiece The Cabinet of Dr Caligari. He was Cesare, plaything of the sinister Caligari, owner of a stand in a traveling fair that visits a small German town. The townsfolk are encouraged to ask Cesare questions. One asks how long he will live and gets the reply, 'you will die tomorrow.' Which he promptly does.

The film is most famous today for its groundbreaking art direction, using theatrical set design to create a distorted world of narrow streets and angular buildings, deliberately artificial and exaggerated to represent the nightmarish world of the cursed Cesare.

Fittingly, it also predicted the future, with Caligari a premonition of another charismatic madman on the horizon and Cesare the German people, all too easily sleepwalked into atrocity.

That's the trouble with letting dreams into the world, y'see. Pretty soon you don't know what's real anymore, what's true. And as Dostoevsky made clear in The Brothers Karamazov: if nothing is true, then everything is permitted.

Eighty years later and another somnambulist is manipulated by a sinister figure to commit a series of crimes. In Richard Kelly's Donnie Darko, troubled teen Donnie's sleep-visions of a giant rabbit also give him access to the future, not the death of individuals this time but the death of everyone, the end of the world. Of course, in the film's quantum time, the possibility exists that Donnie is both dead and alive at the same time, like Schrodinger's Cat, suspended in a dream state between knowing and imagining. Either way, sleep remains a dangerous mystery, that place on old maps yet to be fully explored, where superstitious cartographers usually wrote:

here be monsters.

Monday, August 9, 2010

The Mirror of Dream

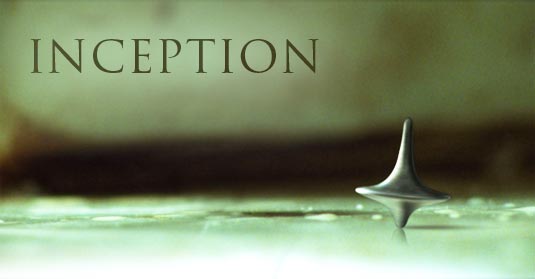

I honestly can't remember the last time I went to my local Omniplex (for a grown-up film I mean, I take my kids all the time.) Tragically that omni- is more spin than fact when it comes to the variety of films on offer. So it was a double pleasure to see Inception last week, partly because it was a blockbuster that demanded you paid attention, but also I'd almost forgotton the mind-altering magic of losing yourself in the dark, succumbing to the dream-world of the screen so completely that it clings to you afterwards, the mind still in suspension, half-believing the streets would rise up like a child's pop-up book and fold over our heads at any minute.

The film is a sci-fi thriller about our unconscious dream-worlds and how technology has figured out how to access them. But at the same time it's a meta-experience for the audience because the film itself is a dream we're all experiencing. In it, Leonardo DiCaprio's character keeps a spinning top as a 'totem'. If it keeps turning, he's still in the dream, if it loses momentum and falls over, he's back in reality. Maybe the audience should be encouraged to bring their own totems so afterwards they could double check they're actually back in the real world, despite what their minds might be telling them.

Ever since I've been thinking about cinema and dreams. The similarity between the two has been obvious since the very earliest days of the medium. Writing of Jean Cocteau in his Biographical Dictionary of Film David Thomson noted that 'Cocteau's overriding image of the poet's passing through the mirror of dream...is a very suggestive metaphor for the way a movie audience can pass into the celluloid domain.' In fact, it's almost as if cinema had to come into existence to satify the growing desire for that domain.

The nineteenth century was full of prefiguring images, of doors into secret gardens and mirrors into alternative realities. When Proust wrote that 'if a little dreaming is dangerous, the cure for it is not to dream less but to dream more, to dream all the time,' he might well have been talking about the movies. They released that insatiable craving for escape, for the refuge of dream states, that had been the subconscious hallmark of the century preceeding it, the century that seemed to will psychoanalysis and cinema into being at more or less the same time and for more or less the same reason, to give us access to our dreams.

'Alice falls asleep in a wood and dreams she sees a white rabbit, which she follows down a rabbit hole...' The mirror of dream could, of course, be an alternative title for Lewis Carroll's sequel to his quintessential Victorian fantasy Alice in Wonderland. It's appropriate then (or inevitable) that one of the earliest British fantasy films was this version of Alice In Wonderland, made in 1903, just two years after Victoria's death. The last surviving copy has been preserved and restored by the BFI. It's a fascinating document, still strangely enchanting, mainly due to, rather than inspite of, the severely damaged nature of the print. The wavering blotchiness, the kinetic erosion, the sudden jumps in time, all give it the feeling of a dream or a ghostly window into another time. It's a feeling helped in no small measure by the modern soundtrack, Samuele De Marchi's Persistence of Vision which is suitably ethereal and otherworldy.

'Do you mean you've never ever spoken to time?' 'No.' 'But ah, she knows how to beat time.' 'When I play music.' 'That accounts for it Alice. He won't stand beating y'know.'

Sixty years later, playwright Dennis Potter had an inspired notion; what if Alice Liddell, the real girl behind Alice in Wonderland, had, as an old woman, been invited to New York on the centenary of Lewis Carroll's birth to receive an honourary degree? The result was his play Alice, which twenty years later became the 1985 film Dreamchild. Potter understood the allure of fantasy and our shaky hold on reality better than most and aided by the wonderful puppetry of Jim Henson created a brilliant and disturbing meditation on memory, fantasy and the dream-states of story-telling and old age.

The film is a sci-fi thriller about our unconscious dream-worlds and how technology has figured out how to access them. But at the same time it's a meta-experience for the audience because the film itself is a dream we're all experiencing. In it, Leonardo DiCaprio's character keeps a spinning top as a 'totem'. If it keeps turning, he's still in the dream, if it loses momentum and falls over, he's back in reality. Maybe the audience should be encouraged to bring their own totems so afterwards they could double check they're actually back in the real world, despite what their minds might be telling them.

Ever since I've been thinking about cinema and dreams. The similarity between the two has been obvious since the very earliest days of the medium. Writing of Jean Cocteau in his Biographical Dictionary of Film David Thomson noted that 'Cocteau's overriding image of the poet's passing through the mirror of dream...is a very suggestive metaphor for the way a movie audience can pass into the celluloid domain.' In fact, it's almost as if cinema had to come into existence to satify the growing desire for that domain.

The nineteenth century was full of prefiguring images, of doors into secret gardens and mirrors into alternative realities. When Proust wrote that 'if a little dreaming is dangerous, the cure for it is not to dream less but to dream more, to dream all the time,' he might well have been talking about the movies. They released that insatiable craving for escape, for the refuge of dream states, that had been the subconscious hallmark of the century preceeding it, the century that seemed to will psychoanalysis and cinema into being at more or less the same time and for more or less the same reason, to give us access to our dreams.

'Alice falls asleep in a wood and dreams she sees a white rabbit, which she follows down a rabbit hole...' The mirror of dream could, of course, be an alternative title for Lewis Carroll's sequel to his quintessential Victorian fantasy Alice in Wonderland. It's appropriate then (or inevitable) that one of the earliest British fantasy films was this version of Alice In Wonderland, made in 1903, just two years after Victoria's death. The last surviving copy has been preserved and restored by the BFI. It's a fascinating document, still strangely enchanting, mainly due to, rather than inspite of, the severely damaged nature of the print. The wavering blotchiness, the kinetic erosion, the sudden jumps in time, all give it the feeling of a dream or a ghostly window into another time. It's a feeling helped in no small measure by the modern soundtrack, Samuele De Marchi's Persistence of Vision which is suitably ethereal and otherworldy.

'Do you mean you've never ever spoken to time?' 'No.' 'But ah, she knows how to beat time.' 'When I play music.' 'That accounts for it Alice. He won't stand beating y'know.'

Sixty years later, playwright Dennis Potter had an inspired notion; what if Alice Liddell, the real girl behind Alice in Wonderland, had, as an old woman, been invited to New York on the centenary of Lewis Carroll's birth to receive an honourary degree? The result was his play Alice, which twenty years later became the 1985 film Dreamchild. Potter understood the allure of fantasy and our shaky hold on reality better than most and aided by the wonderful puppetry of Jim Henson created a brilliant and disturbing meditation on memory, fantasy and the dream-states of story-telling and old age.

Sunday, August 1, 2010

Big Bang Boom

My sister sent me this a few weeks ago but I only got round to watching it today. It's wall-painted animation using time-lapse photography on real locations telling the 'unscientific' story of evolution from the Big Bang to 'how it could probably end'. Very impressive. Animation continues its own evolution.

BIG BANG BIG BOOM from blu on Vimeo.

Thursday, July 22, 2010

Last Five Films You've Seen #3

1. Kingdom of Heaven (2005)

Wasn't impressed with Kingdom Of Heaven on its initial release. It seemed overlong, confused and fatally undermined by the miscasting of Orlando Bloom. All of which is still true and yet, watching it now, I wasn't inclined to be as hard on it. Not that it's suddenly revealed as an unfairly maligned masterpiece or anything, far from it, but I think films, like people, can often grow into their flaws, or rather, the flaws can grow into them, becoming part of what they are. We end up accepting them like we'd accept the character failings of a relative or friend, eventually barely noticing them.

For example, as the political era it was made in recedes from us like a fevered dream, the film's many references to post 9/11 wars and attitudes now seem less thumpingly obvious and more part of an overall humanist thrust. Bloom remains anaemic at best, of course, but I did appreciate the film's visual style better this time around. It's ravishing at times, but all those burnished shots of desert armies, bustling sea ports and medieval villages do start to blend into each other after a while, like glossy illustrations in an expensive picture book, the images left increasingly empty as the human story suffers from simplistic gestures and choppy narrative. And yet, despite that, there's a rich sense of time and place, of religious and political tumult, of having been on an epic journey by the end.

2. In The Heat of the Night (1967)

The social and political times in which In The Heat Of The Night was made have receded too, of course. You've got to remind yourself while watching it now of what was happening in America at the time, that the notion of a black cop from the north joining forces with a Southern sheriff was more than just a good oppositional set-up, a buddy movie contrivance, like Eddie Murphy and Nick Nolte in 48 Hours. (Whatever the merits of that film, no-one's claiming it as a milestone in race relations). No, when this film came out there was real heat in the American night, the heat of Klan torches and race riot burnings. Which probably accounts for why it remains an absorbing thriller to this day. Beneath the routine murder mystery plot and the enjoyable sparring of Tibbs (Poitier) and Gillespie (Steiger) the dangerous energy of the times can still be felt. Norman Jewison's taut, unhurried direction helps, as does the acting, especially Steiger, in an Oscar-winning performance, making a belligerent sheriff sympathetic even as he's being racist and jumping to one wrong conclusion after another. That's star power for you. He's also having fun with the music of the southern accent. Just listen to the way he makes the line 'I've got the motive which is money and the body which is dead!' sing like found poetry. Liberal fantasy entertainment then, contrived to make the black cop win maybe but the set-up's so satisfying you'll happily watch it every time.

3. An Education(2009)

Although set in the drab, conformist world of post-war England, (just before the Swinging Sixties revolution swept it away), the question at the heart of An Education still resonates. University life or the university of life? That's the choice facing sixteen-year-old Jenny (Carey Mulligan), being fast-tracked to Oxford by her aspirational parents. In her bedroom though she listens to French pop songs and dreams of romance and adventure.

Then one day she accepts a lift from charming older man David (Peter Sarsgaard) and a different kind of education enters her life, one that involves fancy restaurants, glamorous clubs and goodnight kisses in expensive cars. Suddenly her life before David seems unbearably static and she's soon in open revolt against what's expected of her, that life of improving education mapped out by well-meaning parents. After all, if action is character, as her English teacher has told her, then what kind of character can come from a life of study? 'If we never did anything we wouldn't be anybody', she argues with some justification. That's the fascinating crux of this film. How to balance the benefits of education against what it asks of you. Is it worth it if, in order to have 'a future', you have to mortgage your youth away studying Latin?

And while the film follows this idea it's genuinely engaging. Unfortunately the filmmakers don't believe it. Like sensible adults they understand that if it's a choice between female empowerment or silly schoolgirl crushes then in the long run its better for the girl to fulfill her potential than throw her life away.

Obviously this is true, but that's not how the film plays for long stretches. In Jenny's empassioned speeches against her education you can feel her realising that living for the moment, feeling alive now is what matters, not the social status of an Oxford education. 'It's not enough to educate us anymore Ms. Walters,' she demands of her headmistress at one stage. 'You've got to tell us why you're doing it'. This is the question the film ultimately fudges.

You can't help feeling if it had been a French film they'd have had the courage of their convictions, allowing Jenny the full consequences of her actions rather than saving her (from herself) at the last minute, cowed back into line by betrayal (David's and the film's).

It's still a good film though, despite this. Carey Mulligan is clearly a star. Peter Sarsgard is all soft-spoken charm. Alfred Molina does a fine job as Jenny's Dad and Rosamund Pike steals every scene she's in as ditzy, good-time girl Helen. Ultimately though it's all let down somewhat by that compromised ending.

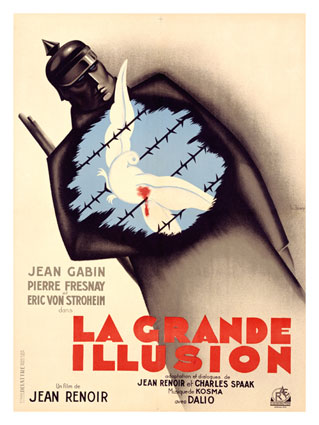

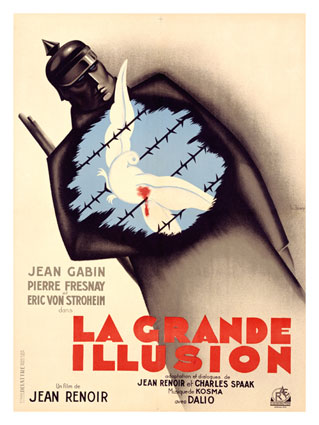

4. La Grande Illusion (1937)

Jean Renoir's La Grande Illusion is one of those imperishable classics everyone should see at least once. It's a POW movie, possibly the first, with all the ingredients we've come to expect from them; tunnel escapes, camp shows, etc. But it's also far more than that, a masterful study of human relations during wartime, of the way class and religious divisions may be put aside in times of mutual danger, but never really go away, always endure. So Captain De Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay) is an aristocrat while Lieutenant Marechal (Jean Gabin) is a mechanic in civilian life. They're both officers, friends even, full of respect for each other but the wariness never goes away, the ghost of their respective social positions always between them. Compare this to De Boeldieu's relationship with Prison Commandant von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim). Both aristocrats, both familiar with the same pre-war high society, both in truth a little distainful all this bourgouise warmongering. Here class trumps nationalism every time. Renoir weaves many more characters into this network of complex relationships: a wealthy Jew, a music hall actor, an intellectual, a black Senegalese prisoner and finally a widowed farmer's wife (played by the wonderful Dita Parlo, star of L'Atalante). Throughout he never puts a foot wrong, creating a compelling war movie and a humanist masterpiece grounded in realism. It leaves you feeling priviledged to have seen it.

5. Star Wars (1977)

The original. I refuse to call it Episode IV: A New Dawn because that's what Lucas wants me to do. This isn't the fourth film it's the first. My kids had been pestering me for ages to see it after they got The Clone Wars on DVD for Christmas. I didn't intend watching it myself but got sucked in. It's the physicality I like still, the sense of actual space and noise, much of it filmed in Tunisia, not created by computers. I've written here before about the camera moving through real space. I think we respond to that in a subconscious way. The sounds, the sense of space, the inescapable feeling of people playing dress-up about it all. Overrated yes, malign influence, undoubtedly, but still retains enough of the fun to be diverting.

Wasn't impressed with Kingdom Of Heaven on its initial release. It seemed overlong, confused and fatally undermined by the miscasting of Orlando Bloom. All of which is still true and yet, watching it now, I wasn't inclined to be as hard on it. Not that it's suddenly revealed as an unfairly maligned masterpiece or anything, far from it, but I think films, like people, can often grow into their flaws, or rather, the flaws can grow into them, becoming part of what they are. We end up accepting them like we'd accept the character failings of a relative or friend, eventually barely noticing them.

For example, as the political era it was made in recedes from us like a fevered dream, the film's many references to post 9/11 wars and attitudes now seem less thumpingly obvious and more part of an overall humanist thrust. Bloom remains anaemic at best, of course, but I did appreciate the film's visual style better this time around. It's ravishing at times, but all those burnished shots of desert armies, bustling sea ports and medieval villages do start to blend into each other after a while, like glossy illustrations in an expensive picture book, the images left increasingly empty as the human story suffers from simplistic gestures and choppy narrative. And yet, despite that, there's a rich sense of time and place, of religious and political tumult, of having been on an epic journey by the end.

2. In The Heat of the Night (1967)

The social and political times in which In The Heat Of The Night was made have receded too, of course. You've got to remind yourself while watching it now of what was happening in America at the time, that the notion of a black cop from the north joining forces with a Southern sheriff was more than just a good oppositional set-up, a buddy movie contrivance, like Eddie Murphy and Nick Nolte in 48 Hours. (Whatever the merits of that film, no-one's claiming it as a milestone in race relations). No, when this film came out there was real heat in the American night, the heat of Klan torches and race riot burnings. Which probably accounts for why it remains an absorbing thriller to this day. Beneath the routine murder mystery plot and the enjoyable sparring of Tibbs (Poitier) and Gillespie (Steiger) the dangerous energy of the times can still be felt. Norman Jewison's taut, unhurried direction helps, as does the acting, especially Steiger, in an Oscar-winning performance, making a belligerent sheriff sympathetic even as he's being racist and jumping to one wrong conclusion after another. That's star power for you. He's also having fun with the music of the southern accent. Just listen to the way he makes the line 'I've got the motive which is money and the body which is dead!' sing like found poetry. Liberal fantasy entertainment then, contrived to make the black cop win maybe but the set-up's so satisfying you'll happily watch it every time.

3. An Education(2009)

Although set in the drab, conformist world of post-war England, (just before the Swinging Sixties revolution swept it away), the question at the heart of An Education still resonates. University life or the university of life? That's the choice facing sixteen-year-old Jenny (Carey Mulligan), being fast-tracked to Oxford by her aspirational parents. In her bedroom though she listens to French pop songs and dreams of romance and adventure.

Then one day she accepts a lift from charming older man David (Peter Sarsgaard) and a different kind of education enters her life, one that involves fancy restaurants, glamorous clubs and goodnight kisses in expensive cars. Suddenly her life before David seems unbearably static and she's soon in open revolt against what's expected of her, that life of improving education mapped out by well-meaning parents. After all, if action is character, as her English teacher has told her, then what kind of character can come from a life of study? 'If we never did anything we wouldn't be anybody', she argues with some justification. That's the fascinating crux of this film. How to balance the benefits of education against what it asks of you. Is it worth it if, in order to have 'a future', you have to mortgage your youth away studying Latin?

And while the film follows this idea it's genuinely engaging. Unfortunately the filmmakers don't believe it. Like sensible adults they understand that if it's a choice between female empowerment or silly schoolgirl crushes then in the long run its better for the girl to fulfill her potential than throw her life away.

Obviously this is true, but that's not how the film plays for long stretches. In Jenny's empassioned speeches against her education you can feel her realising that living for the moment, feeling alive now is what matters, not the social status of an Oxford education. 'It's not enough to educate us anymore Ms. Walters,' she demands of her headmistress at one stage. 'You've got to tell us why you're doing it'. This is the question the film ultimately fudges.

You can't help feeling if it had been a French film they'd have had the courage of their convictions, allowing Jenny the full consequences of her actions rather than saving her (from herself) at the last minute, cowed back into line by betrayal (David's and the film's).

It's still a good film though, despite this. Carey Mulligan is clearly a star. Peter Sarsgard is all soft-spoken charm. Alfred Molina does a fine job as Jenny's Dad and Rosamund Pike steals every scene she's in as ditzy, good-time girl Helen. Ultimately though it's all let down somewhat by that compromised ending.

4. La Grande Illusion (1937)

Jean Renoir's La Grande Illusion is one of those imperishable classics everyone should see at least once. It's a POW movie, possibly the first, with all the ingredients we've come to expect from them; tunnel escapes, camp shows, etc. But it's also far more than that, a masterful study of human relations during wartime, of the way class and religious divisions may be put aside in times of mutual danger, but never really go away, always endure. So Captain De Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay) is an aristocrat while Lieutenant Marechal (Jean Gabin) is a mechanic in civilian life. They're both officers, friends even, full of respect for each other but the wariness never goes away, the ghost of their respective social positions always between them. Compare this to De Boeldieu's relationship with Prison Commandant von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim). Both aristocrats, both familiar with the same pre-war high society, both in truth a little distainful all this bourgouise warmongering. Here class trumps nationalism every time. Renoir weaves many more characters into this network of complex relationships: a wealthy Jew, a music hall actor, an intellectual, a black Senegalese prisoner and finally a widowed farmer's wife (played by the wonderful Dita Parlo, star of L'Atalante). Throughout he never puts a foot wrong, creating a compelling war movie and a humanist masterpiece grounded in realism. It leaves you feeling priviledged to have seen it.

5. Star Wars (1977)

The original. I refuse to call it Episode IV: A New Dawn because that's what Lucas wants me to do. This isn't the fourth film it's the first. My kids had been pestering me for ages to see it after they got The Clone Wars on DVD for Christmas. I didn't intend watching it myself but got sucked in. It's the physicality I like still, the sense of actual space and noise, much of it filmed in Tunisia, not created by computers. I've written here before about the camera moving through real space. I think we respond to that in a subconscious way. The sounds, the sense of space, the inescapable feeling of people playing dress-up about it all. Overrated yes, malign influence, undoubtedly, but still retains enough of the fun to be diverting.

Friday, July 9, 2010

Classic Scene #17

In Cool Hand Luke (1967), Luke is visited in prison by his dying mother. It's a scene bookended by Harry Dean Stanton in the background singing gospel standard Just A Closer Walk With Thee. 'Through this world of toil and snares,' he sings, 'if I falter, Lord, who cares?' The answer to that question is in the same scene when Luke's mother tells him, 'You ain't alone Luke. Everywhere you go I'm with you.' Already then we have the conflation of motherhood and religion, both forms of unconditional love, of shelter and consolation in a crual world. The film's a Christ-allegory, so if Luke is Christ then it makes sense that his chain-smoking old Ma is the Virgin Mary.

Later, informed of her death, he walks to his bunk, picks up his banjo (given to him during that earlier visit) and sings a little boy's idealised vision of his mother, 'a sweet madonna, dressed in rhinestones, sittin' on a pedestal of abalone shell'. Now she's gone though, and he's truly alone in this world.