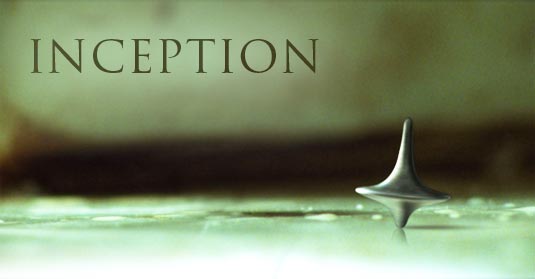

The film is a sci-fi thriller about our unconscious dream-worlds and how technology has figured out how to access them. But at the same time it's a meta-experience for the audience because the film itself is a dream we're all experiencing. In it, Leonardo DiCaprio's character keeps a spinning top as a 'totem'. If it keeps turning, he's still in the dream, if it loses momentum and falls over, he's back in reality. Maybe the audience should be encouraged to bring their own totems so afterwards they could double check they're actually back in the real world, despite what their minds might be telling them.

Ever since I've been thinking about cinema and dreams. The similarity between the two has been obvious since the very earliest days of the medium. Writing of Jean Cocteau in his Biographical Dictionary of Film David Thomson noted that 'Cocteau's overriding image of the poet's passing through the mirror of dream...is a very suggestive metaphor for the way a movie audience can pass into the celluloid domain.' In fact, it's almost as if cinema had to come into existence to satify the growing desire for that domain.

The nineteenth century was full of prefiguring images, of doors into secret gardens and mirrors into alternative realities. When Proust wrote that 'if a little dreaming is dangerous, the cure for it is not to dream less but to dream more, to dream all the time,' he might well have been talking about the movies. They released that insatiable craving for escape, for the refuge of dream states, that had been the subconscious hallmark of the century preceeding it, the century that seemed to will psychoanalysis and cinema into being at more or less the same time and for more or less the same reason, to give us access to our dreams.

'Alice falls asleep in a wood and dreams she sees a white rabbit, which she follows down a rabbit hole...' The mirror of dream could, of course, be an alternative title for Lewis Carroll's sequel to his quintessential Victorian fantasy Alice in Wonderland. It's appropriate then (or inevitable) that one of the earliest British fantasy films was this version of Alice In Wonderland, made in 1903, just two years after Victoria's death. The last surviving copy has been preserved and restored by the BFI. It's a fascinating document, still strangely enchanting, mainly due to, rather than inspite of, the severely damaged nature of the print. The wavering blotchiness, the kinetic erosion, the sudden jumps in time, all give it the feeling of a dream or a ghostly window into another time. It's a feeling helped in no small measure by the modern soundtrack, Samuele De Marchi's Persistence of Vision which is suitably ethereal and otherworldy.

'Do you mean you've never ever spoken to time?' 'No.' 'But ah, she knows how to beat time.' 'When I play music.' 'That accounts for it Alice. He won't stand beating y'know.'

Sixty years later, playwright Dennis Potter had an inspired notion; what if Alice Liddell, the real girl behind Alice in Wonderland, had, as an old woman, been invited to New York on the centenary of Lewis Carroll's birth to receive an honourary degree? The result was his play Alice, which twenty years later became the 1985 film Dreamchild. Potter understood the allure of fantasy and our shaky hold on reality better than most and aided by the wonderful puppetry of Jim Henson created a brilliant and disturbing meditation on memory, fantasy and the dream-states of story-telling and old age.

I had totally forgotten about Dreamchild - another one you've made me want to revisit. Where do you stand on Tim Burton's Alice?

ReplyDeleteI stand on its throat. Not that I've seen it, but I've seen enough of it to know it has all the flaws that made Willy Wonka a woefully misjudged day-glo disaster. I'm afraid me and Tim parted company at Ed Wood. Am now totally fed up of his fatuous 'imagination' along with Johnny Depp's I'm-too-bored-to-do-any-real-acting self-indulgence. They're like a couple of spoilt kids whose overbearing mothers have instilled in them the belief that they can do no wrong. If I was their schooolteacher I'd seperate them for their own good.

ReplyDelete