Wasn't impressed with Kingdom Of Heaven on its initial release. It seemed overlong, confused and fatally undermined by the miscasting of Orlando Bloom. All of which is still true and yet, watching it now, I wasn't inclined to be as hard on it. Not that it's suddenly revealed as an unfairly maligned masterpiece or anything, far from it, but I think films, like people, can often grow into their flaws, or rather, the flaws can grow into them, becoming part of what they are. We end up accepting them like we'd accept the character failings of a relative or friend, eventually barely noticing them.

For example, as the political era it was made in recedes from us like a fevered dream, the film's many references to post 9/11 wars and attitudes now seem less thumpingly obvious and more part of an overall humanist thrust. Bloom remains anaemic at best, of course, but I did appreciate the film's visual style better this time around. It's ravishing at times, but all those burnished shots of desert armies, bustling sea ports and medieval villages do start to blend into each other after a while, like glossy illustrations in an expensive picture book, the images left increasingly empty as the human story suffers from simplistic gestures and choppy narrative. And yet, despite that, there's a rich sense of time and place, of religious and political tumult, of having been on an epic journey by the end.

2. In The Heat of the Night (1967)

The social and political times in which In The Heat Of The Night was made have receded too, of course. You've got to remind yourself while watching it now of what was happening in America at the time, that the notion of a black cop from the north joining forces with a Southern sheriff was more than just a good oppositional set-up, a buddy movie contrivance, like Eddie Murphy and Nick Nolte in 48 Hours. (Whatever the merits of that film, no-one's claiming it as a milestone in race relations). No, when this film came out there was real heat in the American night, the heat of Klan torches and race riot burnings. Which probably accounts for why it remains an absorbing thriller to this day. Beneath the routine murder mystery plot and the enjoyable sparring of Tibbs (Poitier) and Gillespie (Steiger) the dangerous energy of the times can still be felt. Norman Jewison's taut, unhurried direction helps, as does the acting, especially Steiger, in an Oscar-winning performance, making a belligerent sheriff sympathetic even as he's being racist and jumping to one wrong conclusion after another. That's star power for you. He's also having fun with the music of the southern accent. Just listen to the way he makes the line 'I've got the motive which is money and the body which is dead!' sing like found poetry. Liberal fantasy entertainment then, contrived to make the black cop win maybe but the set-up's so satisfying you'll happily watch it every time.

3. An Education(2009)

Although set in the drab, conformist world of post-war England, (just before the Swinging Sixties revolution swept it away), the question at the heart of An Education still resonates. University life or the university of life? That's the choice facing sixteen-year-old Jenny (Carey Mulligan), being fast-tracked to Oxford by her aspirational parents. In her bedroom though she listens to French pop songs and dreams of romance and adventure.

Then one day she accepts a lift from charming older man David (Peter Sarsgaard) and a different kind of education enters her life, one that involves fancy restaurants, glamorous clubs and goodnight kisses in expensive cars. Suddenly her life before David seems unbearably static and she's soon in open revolt against what's expected of her, that life of improving education mapped out by well-meaning parents. After all, if action is character, as her English teacher has told her, then what kind of character can come from a life of study? 'If we never did anything we wouldn't be anybody', she argues with some justification. That's the fascinating crux of this film. How to balance the benefits of education against what it asks of you. Is it worth it if, in order to have 'a future', you have to mortgage your youth away studying Latin?

And while the film follows this idea it's genuinely engaging. Unfortunately the filmmakers don't believe it. Like sensible adults they understand that if it's a choice between female empowerment or silly schoolgirl crushes then in the long run its better for the girl to fulfill her potential than throw her life away.

Obviously this is true, but that's not how the film plays for long stretches. In Jenny's empassioned speeches against her education you can feel her realising that living for the moment, feeling alive now is what matters, not the social status of an Oxford education. 'It's not enough to educate us anymore Ms. Walters,' she demands of her headmistress at one stage. 'You've got to tell us why you're doing it'. This is the question the film ultimately fudges.

You can't help feeling if it had been a French film they'd have had the courage of their convictions, allowing Jenny the full consequences of her actions rather than saving her (from herself) at the last minute, cowed back into line by betrayal (David's and the film's).

It's still a good film though, despite this. Carey Mulligan is clearly a star. Peter Sarsgard is all soft-spoken charm. Alfred Molina does a fine job as Jenny's Dad and Rosamund Pike steals every scene she's in as ditzy, good-time girl Helen. Ultimately though it's all let down somewhat by that compromised ending.

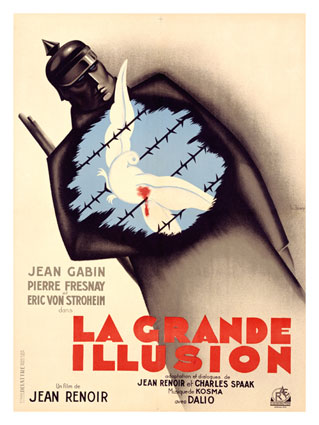

4. La Grande Illusion (1937)

Jean Renoir's La Grande Illusion is one of those imperishable classics everyone should see at least once. It's a POW movie, possibly the first, with all the ingredients we've come to expect from them; tunnel escapes, camp shows, etc. But it's also far more than that, a masterful study of human relations during wartime, of the way class and religious divisions may be put aside in times of mutual danger, but never really go away, always endure. So Captain De Boeldieu (Pierre Fresnay) is an aristocrat while Lieutenant Marechal (Jean Gabin) is a mechanic in civilian life. They're both officers, friends even, full of respect for each other but the wariness never goes away, the ghost of their respective social positions always between them. Compare this to De Boeldieu's relationship with Prison Commandant von Rauffenstein (Erich von Stroheim). Both aristocrats, both familiar with the same pre-war high society, both in truth a little distainful all this bourgouise warmongering. Here class trumps nationalism every time. Renoir weaves many more characters into this network of complex relationships: a wealthy Jew, a music hall actor, an intellectual, a black Senegalese prisoner and finally a widowed farmer's wife (played by the wonderful Dita Parlo, star of L'Atalante). Throughout he never puts a foot wrong, creating a compelling war movie and a humanist masterpiece grounded in realism. It leaves you feeling priviledged to have seen it.

5. Star Wars (1977)

The original. I refuse to call it Episode IV: A New Dawn because that's what Lucas wants me to do. This isn't the fourth film it's the first. My kids had been pestering me for ages to see it after they got The Clone Wars on DVD for Christmas. I didn't intend watching it myself but got sucked in. It's the physicality I like still, the sense of actual space and noise, much of it filmed in Tunisia, not created by computers. I've written here before about the camera moving through real space. I think we respond to that in a subconscious way. The sounds, the sense of space, the inescapable feeling of people playing dress-up about it all. Overrated yes, malign influence, undoubtedly, but still retains enough of the fun to be diverting.