Tuesday, December 15, 2009

French Classics For Free!

Those of you who saw our screening of Godard's evergreen classic A Bout de Souffle last week, will be delighted to know that film site The Auteurs is running a week of classic 60s French films for free all this week. You may have to join the site first but nevertheless, it's serendipity people, and I for one will be watching as many as I can while smoking non-stop, pondering the impossibility of love, sloshing back wine and forgiving Thierry Henry (kind of).

Friday, December 4, 2009

Friday Shorts #2

Ramona Falls "I Say Fever" from Barsuk Records on Vimeo.

This week we have a music video from the band Ramona Falls. Why's it on a film blog? Because it's directed by a guy called Stefan Nadelman, who has a Sundance prize for his 22 minute film Terminal Bar, so he's a proper filmmaker and secondly, it's an astonishingly brilliant music video. In fact, the term 'music video' seems entirely inadequate to describe it. A mind-bendingly dark and imaginative short film would be more accurate, which just happens to have a song attached to it (a very good song too). Enjoy!

Friday, November 27, 2009

Friday Shorts #1

I don't know what you call them really, fan videos, I suppose, that youtube sub-genre of people editing clips from favourite films to music or giving favourite songs a new video. Most of them are uploaded just to show the person loves this film/song, which is fair enough, but some are genuine attempts to create something fresh, to capture the essence of the story or lyrics.

Here are two of my favourites; the first from RubyTuesday717 who has managed to find music capable of doing justice to what is, arguably, the most profoundly heartbreaking film ever made, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

And this from Captainmcglue, finding metaphorical riches in the lush romanticism of Richard Hawley's Open Up Your Door. Enjoy!

Here are two of my favourites; the first from RubyTuesday717 who has managed to find music capable of doing justice to what is, arguably, the most profoundly heartbreaking film ever made, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

And this from Captainmcglue, finding metaphorical riches in the lush romanticism of Richard Hawley's Open Up Your Door. Enjoy!

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

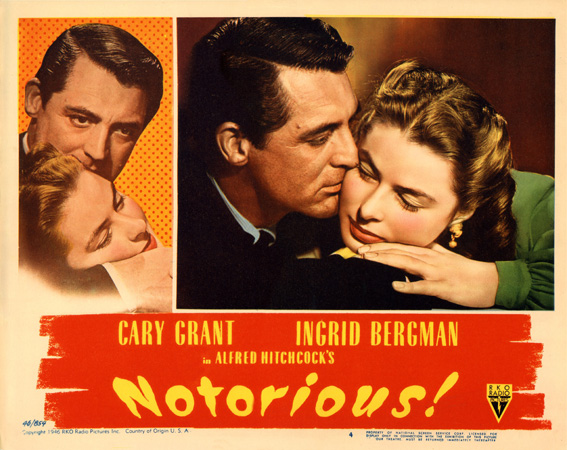

Ten thoughts inspired by: Notorious

1. First of all, there's the symbiotic dance between directors and actors. Many of the best directors, those interested in psychological states, often struggle if they haven't got the right actors. Look at how often Hitchcock's lesser films are saddled with actors ill-suited to the roles, actors with no depth to begin with or whose guarded personas don't allow him anything to mine. (Think of Paul Newman in Torn Curtain). Look at how his well-known yen for beautiful actresses is matched in every respect by actors who brought the best out of him, Cary Grant and James Stewart mainly, but also Joseph Cotten,(Shadow of a Doubt) Robert Walker,(Strangers on a Train) and Barry Foster (Frenzy) to name just a few.

2. Look at how Hitchcock brings out things in these actors no-one else did, but equally, look at the riches flowing the other way too. He needed them, these conduits into transgressive areas. When he was lucky enough to get them he was brilliant at finding their hidden dark sides, all that alienation, misanthropy and self-hatred not far from the surface of charming exteriors (Cotten, Walker & Foster), how easily Stewart's pious do-goodery, his martyr's passion for justice could tip over into obsessiveness and destruction.

3. In Notorious he strips away Grant's easy charm, strips away 'Cary Grant' really, leaving this sauve husk, this dangerous void, (think of the first time we see Devlin in the film, just the back of his head, ominously watching the other party revellers). As an Englishman Hitchcock would have been more aware than most of the constructed nature of Grant's Hollywood persona, of the real Cockney hiding behind it, the slum-dog acrobat Archibald Leach. Surely the day he met Grant was the day he began to be fascinated by what's hidden behind charming exteriors?

4. Hitchcock's relationship with his screen women is no less fascinating and collaborative. Sure it graduated towards sadism in his later years but in the 40s it was romantic, an exploration of emotional complexity and a product of the natures of the actresses he worked with, mainly Ingrid Bergman.

5. No actress gave herself up to suffering like Bergman. Vulnerability, defiance, self-hatred, sadness, bravery, watch her take on all of these and more in Notorious, from drunken floozy to endangered heroine, beautiful all the way. You can sense Hitchcock's spellbound fascination with her, not just visually, but emotionally too, the way she's leading the film into places it might not have gone without her. Imagine what kind of film it would've been with a different actress, Rita Hayworth, say, or Jean Arthur?

6. Then there are those poor forgotten puppies of the movie business, the writers. Consider that Notorious was written by Ben Hecht, probably the geatest screenwriter of the golden age of Hollywood. He seems to have brought a new seriousness to Hitchcock, a grown-up respect for emotional terrain, for the classical marriage of form and content. You feel that everyone's on their game because Hecht has given them something better than usual. You also feel that part of what makes Notorious work so well are the details. Hitchcock was frequently sloppy when it came to details, openly deriding the plot devices (the famous McGuffins) at the centre of his movies. You sense that Hecht, that good newspaper man at heart, researched his locations and made sure the McGuffin here, uranium hidden in wine bottles, had a hint of truth to it (a year before the first atomic bomb was detonated.)

7. And don't forget the sly pleasures of Claude Rains. He's every bit as complex a character as the leads. With a little tweaking it could easily be his film, poor man, trapped by evil Nazi cronies who'll kill him at the slightest hint of betrayal, in love with a woman who turns out to be a spy and in thrall to a vicious, manipulative mother, forced to be a Nazi when all he really wants to be is a playboy, as charming and witty as Claude Rains.

8. And then there's patriotism, the last refuge of the scoundral. Devlin is seemingly willing to let the woman he loves whore herself for a greater cause, for the greater good. Is he right or wrong to do this? If this was post 9/11 rather than post WW11 would it look any better? And is it really patriotism or something else entirely, a desire to punish her for all those men she's slept with before him. Notice the cold way he looks at her sometimes. She's making him weak and he hates her for it, complicating everything, the simple certainties of good and evil, of allegience to job and country, of knowing who the enemies are. He looks at her and all certainty disappears. Only love can do this. It's superbly complicated, the kind of love rarely seen in Hollywood movies, then or now.

9. But it is love, and despite all its noir darkness this is a very romantic film. So let's not forget the famous, Hay's Code defying, extended kiss, a genius scene capturing the true carnal pleasure of lovers, all nuzzling little kisses and the addiction of closeness.

10. And finally, there's the truth of the camera, Hitchcock's eternal belief in movement for its own sake, for the pleasure of it, yes, but also for the way it could illustrate thoughts, feelings and situations better than anything Ben Hecht or anyone else could conjure up in words. So see it give you set-up and secret in one elegant swoop from staircase longshot to key-in-hand close-up or watch it thrillingly capture the heart-in-mouth shock of discovering your husband and his mother have been poisoning you by zooming into their smug, conniving faces.

Saturday, September 26, 2009

The Film Club Reviews #4

Anvil! The Story Of Anvil (2008)

Here at the film club we've endevoured to show good documentaries from the off. My club compadre, in particular, is an enthusiastic advocate for them. And while I nearly always enjoy them, I have to admit they don't float my boat as much as a truly great fictional movie does. I don't really know why. But as we're showing three documentaries this season, it's made me think about my response to them which is, not ambivalent exactly, but certainly not as openly moved and provoked by them as others seem to be. So why is this? Well, maybe it's this strange place they occupy between reality and artifice. The first film we showed this season was a case in point, Anvil: The Story of Anvil.

As enjoyable and amusing as it undoubtedly is I came away with these nagging questions. For starters, was it all an elaborate hoax? No, it's clear Anvil were an 80s metal band who fell by the wayside. Oh good, so it's all real then. Well, hmmm, is it though, or were the filmmakers, under the cover of this reality, playing fast and loose with events, manipulating them to make a better narrative arc? Were they exploiting these guys for comic effect, either by editing it that way or setting up semi-improvised scenes of deadpan farce?

And the question hovering over all others, if they were doing this, was that a bad thing? Didn't it result in a hugely enjoyable, uplifting film? Yes, it did. So what's the problem?

I don't know exactly, mysterious accusatory voice in my head. Maybe this vague sense of being manipulated stops me fully giving myself up to films like this. The documentary form asks you to take what you see at face value, that's the unspoken contract of the genre, telling it like it is. But the truth is subjective at the best of times and film is an artful construction, edited for effect.

But if it's not real then our emotions are being toyed with, right? In Anvil we're being asked to care about these people, their desperate last-chance attempts to make it big. Our response is naked, human, with no fictional safety net between us and it. Reacting like this is clearly more complicated than with the usual film experience.

Maybe that's a good thing, sure, but maybe in a culture hamstrung by human interest angles and you-too-can-achieve-your-dream cliches it invites us to indulge in the kind of easy emotional catharsis we haven't earned, disarmed under the guise of documentarian truth?

I mean, what is Anvil saying? That the human story behind any phenomena is more important than the quality of that phenomena? Persist long enough and almost anything becomes loveable? Do we admire Lips and Robb? Aren't they just heavy metal versions of the deluded losers on X Factor, hanging on like those Japanese soldiers on islands still convinced the war is going on? Is it admirable they continue to follow their dream? If you knew them would you be proud or embarassed?

We've clearly become a culture obsessed with 'reality', with true life stories, memoirs, reality TV. It's hardly a stretch to see the rise of the documentary as being part of this trend. It's like there's been some kind of collective failure of imagination in the world and a creative cowardice along with it.

Here's what I think: if you have a good story, fictionalise it. It's what truly creative people do, as opposed to what exibitionists do. Fiction allows the reader/viewer to identify, enter in to, become part of the experience. The memoir/documentary often encourages passive gawping. It's a one-way system with only room for the people involved. It's their story, not yours.

Maybe that's it. Either give me the banality of the truly real or the fully immersive artifice of fictional worlds where we can explore our fears, fantasies, ideas and so on rather than just being spectators at someone else's.

(The exception to all this was Man on Wire. A film where the thriller aspect was up front and part of the package. Real life had taken on the contours of a film and the documentary exploited that brilliantly. Plus, the tiny figure of a man on a wire thousands of feet in the air is an image so pregnant with awe and metaphor it's beyond manipulation, like something from a Greek myth).

Here at the film club we've endevoured to show good documentaries from the off. My club compadre, in particular, is an enthusiastic advocate for them. And while I nearly always enjoy them, I have to admit they don't float my boat as much as a truly great fictional movie does. I don't really know why. But as we're showing three documentaries this season, it's made me think about my response to them which is, not ambivalent exactly, but certainly not as openly moved and provoked by them as others seem to be. So why is this? Well, maybe it's this strange place they occupy between reality and artifice. The first film we showed this season was a case in point, Anvil: The Story of Anvil.

As enjoyable and amusing as it undoubtedly is I came away with these nagging questions. For starters, was it all an elaborate hoax? No, it's clear Anvil were an 80s metal band who fell by the wayside. Oh good, so it's all real then. Well, hmmm, is it though, or were the filmmakers, under the cover of this reality, playing fast and loose with events, manipulating them to make a better narrative arc? Were they exploiting these guys for comic effect, either by editing it that way or setting up semi-improvised scenes of deadpan farce?

And the question hovering over all others, if they were doing this, was that a bad thing? Didn't it result in a hugely enjoyable, uplifting film? Yes, it did. So what's the problem?

I don't know exactly, mysterious accusatory voice in my head. Maybe this vague sense of being manipulated stops me fully giving myself up to films like this. The documentary form asks you to take what you see at face value, that's the unspoken contract of the genre, telling it like it is. But the truth is subjective at the best of times and film is an artful construction, edited for effect.

But if it's not real then our emotions are being toyed with, right? In Anvil we're being asked to care about these people, their desperate last-chance attempts to make it big. Our response is naked, human, with no fictional safety net between us and it. Reacting like this is clearly more complicated than with the usual film experience.

Maybe that's a good thing, sure, but maybe in a culture hamstrung by human interest angles and you-too-can-achieve-your-dream cliches it invites us to indulge in the kind of easy emotional catharsis we haven't earned, disarmed under the guise of documentarian truth?

I mean, what is Anvil saying? That the human story behind any phenomena is more important than the quality of that phenomena? Persist long enough and almost anything becomes loveable? Do we admire Lips and Robb? Aren't they just heavy metal versions of the deluded losers on X Factor, hanging on like those Japanese soldiers on islands still convinced the war is going on? Is it admirable they continue to follow their dream? If you knew them would you be proud or embarassed?

We've clearly become a culture obsessed with 'reality', with true life stories, memoirs, reality TV. It's hardly a stretch to see the rise of the documentary as being part of this trend. It's like there's been some kind of collective failure of imagination in the world and a creative cowardice along with it.

Here's what I think: if you have a good story, fictionalise it. It's what truly creative people do, as opposed to what exibitionists do. Fiction allows the reader/viewer to identify, enter in to, become part of the experience. The memoir/documentary often encourages passive gawping. It's a one-way system with only room for the people involved. It's their story, not yours.

Maybe that's it. Either give me the banality of the truly real or the fully immersive artifice of fictional worlds where we can explore our fears, fantasies, ideas and so on rather than just being spectators at someone else's.

(The exception to all this was Man on Wire. A film where the thriller aspect was up front and part of the package. Real life had taken on the contours of a film and the documentary exploited that brilliantly. Plus, the tiny figure of a man on a wire thousands of feet in the air is an image so pregnant with awe and metaphor it's beyond manipulation, like something from a Greek myth).

Friday, September 25, 2009

They Call Them Moving Pictures

"We were all delighted, we all realized we were leaving confusion and nonsense behind and performing our one noble function of the time, move." - Jack Kerouac, On the Road

There's a scene in Murnau's silent classic Sunrise, that I love. I first saw it on the big screen, with a live musical score by the great 3epkano, during the Arts Festival a couple of years ago. I'd been out quite late the night before, just dragged myself shakily to this lunchtime performance, so was feeling a tad fragile, which may or may not have had a baring on my response.

It was the trolley scene that got me. Suddenly the film was doing something unexpected. The camera was still but the sense of movement was exhilerating. We were inside the trolley car with the husband and wife as it travelled from the country, the forest and lake, to the big city. (It's here one min into this clip).

Even if you've never seen the film before you know something is very wrong with this couple. She can't look at him. He can't speak to her. It's a hugely tranformational moment in their lives. Everything hangs in the balance. Everything she's known has just vanished before her eyes. How has it come to this? In the darkness of the trolley car, all the implications of what has just happened linger as it travels through the forest, by the lake and finally into the city.

It's a beautiful few minutes. The wife's bowed head, almost like she's dreaming everything behind her, the tram banking round corners, the sudden appearance of the man on the bike, the glimpses of buildings and signs, and then the thrilling almost out of control horse-drawn carriage suddenly pitching into view.

It's a film within a film moment, the movie-house darkness of the trolley acting as a conduit for these dream-images of movement (there's certainly something dream-like about the way the scenes seem perfectly natural and yet the speed of the journey from country to city doesn't seem right at all).

And it made me realise how much the medium exists to do this, move through actual space. Think of those bravura long shots at the beginning of Touch of Evil or Goodfellas. Why do we love these scenes so much? It's the sense of sustained difficulty, sure, but it's also the sense of sustained movement through streets and corridors, around obstacles and crowds, that fascinates us.

Think of Kubrick's steadicam prowling the Overlook Hotel in The Shining, or better yet think of this scene from the documentary Soy Cuba (I Am Cuba).

It's an amazing scene, the camera becoming the soul of the dead man rising above the procession (that's how I see it anyway) but beyond that it's amazing simply as a how-did-they-do-that piece of movement, coming close to a definition of what cinema is in essense, the awe of captured movement, taking us straight back to the shock of the Lumiere brothers' brief film of an arriving train exploding nineteenth century notions of time and space.

In this digital age, this CGI age, we're in danger of forgetting this simple lesson, that we respond instinctively, in a purely human way, to seeing space and movement through the kino-eye. As the quote above suggests, it allows us to leave confusion and nonsense behind, watching a film perform its one noble function, to move.

There's a scene in Murnau's silent classic Sunrise, that I love. I first saw it on the big screen, with a live musical score by the great 3epkano, during the Arts Festival a couple of years ago. I'd been out quite late the night before, just dragged myself shakily to this lunchtime performance, so was feeling a tad fragile, which may or may not have had a baring on my response.

It was the trolley scene that got me. Suddenly the film was doing something unexpected. The camera was still but the sense of movement was exhilerating. We were inside the trolley car with the husband and wife as it travelled from the country, the forest and lake, to the big city. (It's here one min into this clip).

Even if you've never seen the film before you know something is very wrong with this couple. She can't look at him. He can't speak to her. It's a hugely tranformational moment in their lives. Everything hangs in the balance. Everything she's known has just vanished before her eyes. How has it come to this? In the darkness of the trolley car, all the implications of what has just happened linger as it travels through the forest, by the lake and finally into the city.

It's a beautiful few minutes. The wife's bowed head, almost like she's dreaming everything behind her, the tram banking round corners, the sudden appearance of the man on the bike, the glimpses of buildings and signs, and then the thrilling almost out of control horse-drawn carriage suddenly pitching into view.

It's a film within a film moment, the movie-house darkness of the trolley acting as a conduit for these dream-images of movement (there's certainly something dream-like about the way the scenes seem perfectly natural and yet the speed of the journey from country to city doesn't seem right at all).

And it made me realise how much the medium exists to do this, move through actual space. Think of those bravura long shots at the beginning of Touch of Evil or Goodfellas. Why do we love these scenes so much? It's the sense of sustained difficulty, sure, but it's also the sense of sustained movement through streets and corridors, around obstacles and crowds, that fascinates us.

Think of Kubrick's steadicam prowling the Overlook Hotel in The Shining, or better yet think of this scene from the documentary Soy Cuba (I Am Cuba).

It's an amazing scene, the camera becoming the soul of the dead man rising above the procession (that's how I see it anyway) but beyond that it's amazing simply as a how-did-they-do-that piece of movement, coming close to a definition of what cinema is in essense, the awe of captured movement, taking us straight back to the shock of the Lumiere brothers' brief film of an arriving train exploding nineteenth century notions of time and space.

In this digital age, this CGI age, we're in danger of forgetting this simple lesson, that we respond instinctively, in a purely human way, to seeing space and movement through the kino-eye. As the quote above suggests, it allows us to leave confusion and nonsense behind, watching a film perform its one noble function, to move.

Labels:

goodfellas,

kubrick,

lumiere,

murnau,

shining,

soy cuba,

sunrise,

They Call Them Moving Pictures,

touch of evil

Wednesday, June 17, 2009

The Film Club Reviews #3

L'Atalante (1932)

Jean Vigo was the first poet of modern cinema. Of course there were great directors of the silent era like Murnau and Lang, but their emotional range was rarely much above Victorian dime-store romances, morality plays or crime novels.

Vigo was different. He brought a modern indifference to absolutes and types, a dreamer's knowledge of inner states, a realist's understanding of the complexity of desire and a romantic's eye for the beauty of industrial landscapes and plain country girls. And he did all this with just one full-length film, L'Atalante, the first film we showed when we began the film club in 2007. A statement of intent. Either you understood or you didn't. Not that we picked it for that reason but it worked out that way.

Many of the 120 people who turned up clearly thought we were resurrecting the old film club and all the social implications of that. What they got were two relative nobodies with poor networking skills and absolutely no snob value at all. Oh and a film often voted one of the best ever made. Shouldn't that have been enough?

Maybe they couldn't see passed the love of mood over contrived drama, maybe it didn't tell them what to think, or maybe it just didn't pander to the kind of romantic narrative we've become used to, the kind perfected at much the same time by Frank Capra in It Happened One Night.

Pretty heiress on the run meets tough-guy reporter and they bicker all the way to a happy ending. In fairness, it's a great film, but it ends where real life takes over, before the question can be asked. How could these two live together after the adventure of their 'meet cute' has ended?

L'Atalante begins there. The happy couple, marching through the village on their wedding day. It's the kind of procession that would end a Jane Austen adaption. But it's part of this film's emotional realism to want to explore the difficulties of maintaining love after the inital flush of romance.

The courtship has obviously been swift. This girl trapped in a small village dreaming of escape meets a handsome(ish) bargeman. It's surely part of the attraction for her. The excitement of escape.

But soon the monotonous day to day routine of barge life begins to bore her and resentment grows towards her husband for not being whatever she imagined him to be. Add in the unsettling, brute presence of the old seadog, Jules, fascinating and frightening her with his tattoos and gruffness, and it's not surprising her head is turned by another man and dreams of big city life.

It's a river journey film, (name me a bad one), with water as a symbol of poetic vision, a metaphor for the search for love. And it's full of the shyness and yearning of desire. But unlike Murnau's Sunrise, say, L'Atalante locates sexuality within the marriage not outside it, another sign of it's modern sensibility. Tragically Vigo died soon after making this, the original DNA of European cinema, as if its perfection left him with nowhere else to go. We should all be so lucky to leave behind such a fitting epitaph.

Jean Vigo was the first poet of modern cinema. Of course there were great directors of the silent era like Murnau and Lang, but their emotional range was rarely much above Victorian dime-store romances, morality plays or crime novels.

Vigo was different. He brought a modern indifference to absolutes and types, a dreamer's knowledge of inner states, a realist's understanding of the complexity of desire and a romantic's eye for the beauty of industrial landscapes and plain country girls. And he did all this with just one full-length film, L'Atalante, the first film we showed when we began the film club in 2007. A statement of intent. Either you understood or you didn't. Not that we picked it for that reason but it worked out that way.

Many of the 120 people who turned up clearly thought we were resurrecting the old film club and all the social implications of that. What they got were two relative nobodies with poor networking skills and absolutely no snob value at all. Oh and a film often voted one of the best ever made. Shouldn't that have been enough?

Maybe they couldn't see passed the love of mood over contrived drama, maybe it didn't tell them what to think, or maybe it just didn't pander to the kind of romantic narrative we've become used to, the kind perfected at much the same time by Frank Capra in It Happened One Night.

Pretty heiress on the run meets tough-guy reporter and they bicker all the way to a happy ending. In fairness, it's a great film, but it ends where real life takes over, before the question can be asked. How could these two live together after the adventure of their 'meet cute' has ended?

L'Atalante begins there. The happy couple, marching through the village on their wedding day. It's the kind of procession that would end a Jane Austen adaption. But it's part of this film's emotional realism to want to explore the difficulties of maintaining love after the inital flush of romance.

The courtship has obviously been swift. This girl trapped in a small village dreaming of escape meets a handsome(ish) bargeman. It's surely part of the attraction for her. The excitement of escape.

But soon the monotonous day to day routine of barge life begins to bore her and resentment grows towards her husband for not being whatever she imagined him to be. Add in the unsettling, brute presence of the old seadog, Jules, fascinating and frightening her with his tattoos and gruffness, and it's not surprising her head is turned by another man and dreams of big city life.

It's a river journey film, (name me a bad one), with water as a symbol of poetic vision, a metaphor for the search for love. And it's full of the shyness and yearning of desire. But unlike Murnau's Sunrise, say, L'Atalante locates sexuality within the marriage not outside it, another sign of it's modern sensibility. Tragically Vigo died soon after making this, the original DNA of European cinema, as if its perfection left him with nowhere else to go. We should all be so lucky to leave behind such a fitting epitaph.

Labels:

capra,

film club reviews,

kilkenny,

l'atalante,

murnau,

sunrise,

vigo

The Film Club Reviews #2

The Beat That My Heart Skipped(2005)

One of the finest french films of recent years. It's a remake, of course, of James Tobruk's 1978 movie Fingers which starred the young Harvey Kietel. So why's this so good. Well, first, second and last, there's the star, Romain Duris. He's dynamite in this. It's a star-making turn. He's got to be convincing as a thug-for-hire, flushing illegal-immigrants and squattrers out of buildings and, at the same time, a former piano prodigy trying to rekindle his career. It's borderline absurd and only an actor seething with poetry and violence could pull it off. Kietel, of course, had it in his prime, wandering the mean streets with god and redemption in his soulful eyes. Duris is just as good, if not better. Moody and hypnotic, he gives a performance that's not only intensly physical, but also loaded with wary emotions, private thoughts and twitchy fingers. He's not likeable but you ache for him nonetheless as he can't quite reach the sensitivity required to be a great pianist. Maybe it's been brutalised out of him or maybe he never really had it. Maybe it's just a relic of his past, a way of keeping his dead mother's memory alive. Whatever it is, the anger inside won't let him relax. He insists on hounding the music into submission. Meanwhile his gangster life isn't going away either. Jacques Audiard's direction is superb, all smeary neon and late-night faces lit by muted, dashboard lights. Edited with loose-limbed brilliance, it's a cool urban noir and an engrossing meditation on the mystery of talent.

One of the finest french films of recent years. It's a remake, of course, of James Tobruk's 1978 movie Fingers which starred the young Harvey Kietel. So why's this so good. Well, first, second and last, there's the star, Romain Duris. He's dynamite in this. It's a star-making turn. He's got to be convincing as a thug-for-hire, flushing illegal-immigrants and squattrers out of buildings and, at the same time, a former piano prodigy trying to rekindle his career. It's borderline absurd and only an actor seething with poetry and violence could pull it off. Kietel, of course, had it in his prime, wandering the mean streets with god and redemption in his soulful eyes. Duris is just as good, if not better. Moody and hypnotic, he gives a performance that's not only intensly physical, but also loaded with wary emotions, private thoughts and twitchy fingers. He's not likeable but you ache for him nonetheless as he can't quite reach the sensitivity required to be a great pianist. Maybe it's been brutalised out of him or maybe he never really had it. Maybe it's just a relic of his past, a way of keeping his dead mother's memory alive. Whatever it is, the anger inside won't let him relax. He insists on hounding the music into submission. Meanwhile his gangster life isn't going away either. Jacques Audiard's direction is superb, all smeary neon and late-night faces lit by muted, dashboard lights. Edited with loose-limbed brilliance, it's a cool urban noir and an engrossing meditation on the mystery of talent.

Labels:

audiard,

beat my heart skipped,

film club reviews,

kietel,

romain duris

The Film Club Reviews #1

M. Hulot's Holiday (1952)

This just makes me happy. The sounds, the blissful atmosphere.

Watching it makes me feel like I've been on a holiday, like I've spent a week in another carefree world, so perfectly does it create time and place. I feel refreshed and full of good cheer (ok, so not like a real holiday then, but you know what i mean.) After all, what more could you ask of a film, of any great art, than that it create a perfectly realised world, which exists in its own sweet bubble of eternity?And I haven't even mentioned how funny it is. Hulot's unique tennis serve, the animal rug caught on his boot spur, the numerous instances of simple but perfect slapstick, missed steps, squeeky doors, collapsing canoes. What Tati seems to have understood (unlike the Mr Bean ripoffs) is it's Hulot's sublime impeturbability, his oblivious good nature that makes it so funny. We're not laughing at him, it's not a film version of funniest home movies. We don't pity or dispise him (as i expect even his creators do of Mr Bean), we love Hulot. May he always be on holiday, pipe at a jaunty angle, funny car barping along country roads, pretty girls playing idyllic music from hotel windows, the sea whooshing dreamily in the background. And as long as this film exists, he always will.

This just makes me happy. The sounds, the blissful atmosphere.

Watching it makes me feel like I've been on a holiday, like I've spent a week in another carefree world, so perfectly does it create time and place. I feel refreshed and full of good cheer (ok, so not like a real holiday then, but you know what i mean.) After all, what more could you ask of a film, of any great art, than that it create a perfectly realised world, which exists in its own sweet bubble of eternity?And I haven't even mentioned how funny it is. Hulot's unique tennis serve, the animal rug caught on his boot spur, the numerous instances of simple but perfect slapstick, missed steps, squeeky doors, collapsing canoes. What Tati seems to have understood (unlike the Mr Bean ripoffs) is it's Hulot's sublime impeturbability, his oblivious good nature that makes it so funny. We're not laughing at him, it's not a film version of funniest home movies. We don't pity or dispise him (as i expect even his creators do of Mr Bean), we love Hulot. May he always be on holiday, pipe at a jaunty angle, funny car barping along country roads, pretty girls playing idyllic music from hotel windows, the sea whooshing dreamily in the background. And as long as this film exists, he always will.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)