1. First of all, there's the symbiotic dance between directors and actors. Many of the best directors, those interested in psychological states, often struggle if they haven't got the right actors. Look at how often Hitchcock's lesser films are saddled with actors ill-suited to the roles, actors with no depth to begin with or whose guarded personas don't allow him anything to mine. (Think of Paul Newman in Torn Curtain). Look at how his well-known yen for beautiful actresses is matched in every respect by actors who brought the best out of him, Cary Grant and James Stewart mainly, but also Joseph Cotten,(Shadow of a Doubt) Robert Walker,(Strangers on a Train) and Barry Foster (Frenzy) to name just a few.

2. Look at how Hitchcock brings out things in these actors no-one else did, but equally, look at the riches flowing the other way too. He needed them, these conduits into transgressive areas. When he was lucky enough to get them he was brilliant at finding their hidden dark sides, all that alienation, misanthropy and self-hatred not far from the surface of charming exteriors (Cotten, Walker & Foster), how easily Stewart's pious do-goodery, his martyr's passion for justice could tip over into obsessiveness and destruction.

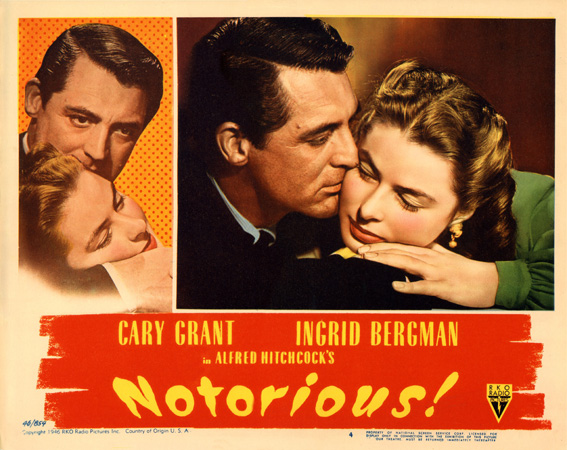

3. In Notorious he strips away Grant's easy charm, strips away 'Cary Grant' really, leaving this sauve husk, this dangerous void, (think of the first time we see Devlin in the film, just the back of his head, ominously watching the other party revellers). As an Englishman Hitchcock would have been more aware than most of the constructed nature of Grant's Hollywood persona, of the real Cockney hiding behind it, the slum-dog acrobat Archibald Leach. Surely the day he met Grant was the day he began to be fascinated by what's hidden behind charming exteriors?

4. Hitchcock's relationship with his screen women is no less fascinating and collaborative. Sure it graduated towards sadism in his later years but in the 40s it was romantic, an exploration of emotional complexity and a product of the natures of the actresses he worked with, mainly Ingrid Bergman.

5. No actress gave herself up to suffering like Bergman. Vulnerability, defiance, self-hatred, sadness, bravery, watch her take on all of these and more in Notorious, from drunken floozy to endangered heroine, beautiful all the way. You can sense Hitchcock's spellbound fascination with her, not just visually, but emotionally too, the way she's leading the film into places it might not have gone without her. Imagine what kind of film it would've been with a different actress, Rita Hayworth, say, or Jean Arthur?

6. Then there are those poor forgotten puppies of the movie business, the writers. Consider that Notorious was written by Ben Hecht, probably the geatest screenwriter of the golden age of Hollywood. He seems to have brought a new seriousness to Hitchcock, a grown-up respect for emotional terrain, for the classical marriage of form and content. You feel that everyone's on their game because Hecht has given them something better than usual. You also feel that part of what makes Notorious work so well are the details. Hitchcock was frequently sloppy when it came to details, openly deriding the plot devices (the famous McGuffins) at the centre of his movies. You sense that Hecht, that good newspaper man at heart, researched his locations and made sure the McGuffin here, uranium hidden in wine bottles, had a hint of truth to it (a year before the first atomic bomb was detonated.)

7. And don't forget the sly pleasures of Claude Rains. He's every bit as complex a character as the leads. With a little tweaking it could easily be his film, poor man, trapped by evil Nazi cronies who'll kill him at the slightest hint of betrayal, in love with a woman who turns out to be a spy and in thrall to a vicious, manipulative mother, forced to be a Nazi when all he really wants to be is a playboy, as charming and witty as Claude Rains.

8. And then there's patriotism, the last refuge of the scoundral. Devlin is seemingly willing to let the woman he loves whore herself for a greater cause, for the greater good. Is he right or wrong to do this? If this was post 9/11 rather than post WW11 would it look any better? And is it really patriotism or something else entirely, a desire to punish her for all those men she's slept with before him. Notice the cold way he looks at her sometimes. She's making him weak and he hates her for it, complicating everything, the simple certainties of good and evil, of allegience to job and country, of knowing who the enemies are. He looks at her and all certainty disappears. Only love can do this. It's superbly complicated, the kind of love rarely seen in Hollywood movies, then or now.

9. But it is love, and despite all its noir darkness this is a very romantic film. So let's not forget the famous, Hay's Code defying, extended kiss, a genius scene capturing the true carnal pleasure of lovers, all nuzzling little kisses and the addiction of closeness.

10. And finally, there's the truth of the camera, Hitchcock's eternal belief in movement for its own sake, for the pleasure of it, yes, but also for the way it could illustrate thoughts, feelings and situations better than anything Ben Hecht or anyone else could conjure up in words. So see it give you set-up and secret in one elegant swoop from staircase longshot to key-in-hand close-up or watch it thrillingly capture the heart-in-mouth shock of discovering your husband and his mother have been poisoning you by zooming into their smug, conniving faces.

This is so good! Makes me desperate to see the movie again. There isn't much debate to be had because you are just right. But I'm interested in what appears to be dig at Paul Newman. Was he ill-suited to the role, missing depth or guarded in Torn Curtain? Would Cary Grant have made that movie interesting or was it a dud anyway? There is indeed a shiftiness to Grant which suits Hitchcock. Perhaps Newman is ill-suited because he's more of a direct man's man type?

ReplyDeletemy argument is it's a dud because the actors were ill-suited to a hitchcock film, not that they were bad actors. julie andrews was the female lead. could you imagine an actress less likely to inspire hitchcock than her? no emotional or sexual complexity at all. and what does a direct man's man type mean? surely newman had doubts, insecurities, secrets? but as an actor he's self consciously 'cool', a post method actor. for hitchcock there's no psychological seam he can mine. that doesn't mean newman didn't have depth as an actor, it was just of a type that was less exploitable.

ReplyDeleteanother thought inspired by all this is it's not really a wise idea to write comments at 1.49am especially after alcohol has been taken. but thankfully the above point is relatively coherent considering. just to add that i love paul newman, and you're right, torn curtain probably would've been a dud even with grant but the lack of chemistry between director and leading actors certainly didn't help matters. that was really my point, the alchemy that happens sometimes where the director's vision and the actor's intuition come together, feed off each other, take the movie somewhere deeper than would happen otherwise. it's the old artist/muse relationship, really. it's what makes notorious so satisfying, the sense of deep fascination, of involvement, not just that hitchcock is projecting the actors' inner vulnerabilities but that they're letting him. it's a trust thing, like lovers. maybe that's it, maybe a self-conscious man's man like newman couldn't let himself be that vulnerable, couldn't let hitchcock make love to him with his camera!

ReplyDeleteHad to buy the DVD just because of your review and have re-read and enjoyed it even more now that the movie is fresh in my mind.

ReplyDelete