Thursday, December 20, 2012

Edit Worthy

'As a filmmaker I'm speaking to you from my home.' His home being the editing suite. He being Orson Welles in his documentary Filming Othello (1978). In our digital age the tactile art of editing film has mostly been lost but this is still gospel. Editing is arguably the true creative process. Everything else is just gathering the ingredients. How you put them together is the real test. As he quotes Carlisle: almost everything examined deeply enough will turn out to be musical. The best artists have an ear for the rhythm of how scenes or sentences flow. An innate feel for how they follow each other. For Welles the moviola is a musical instrument where you search for the right tempo, splicing the images together until the hum, until they reveal an inner harmony, because 'a film is never right until it's right musically.' The pursuit of that rightness can take years. And often sense plays second fiddle to rhythm. Meaning follows form. You understand the shape or rhythm of it long before you understand what it is you're trying to say. In fact, the rhythm can often dictate the meaning. So editing can reveal the greatness waiting inside a film, manifest the dream inside the filmmaker's head, or, as Welles knew only too well, it could gut that greatness like a dead fish.

Saturday, December 8, 2012

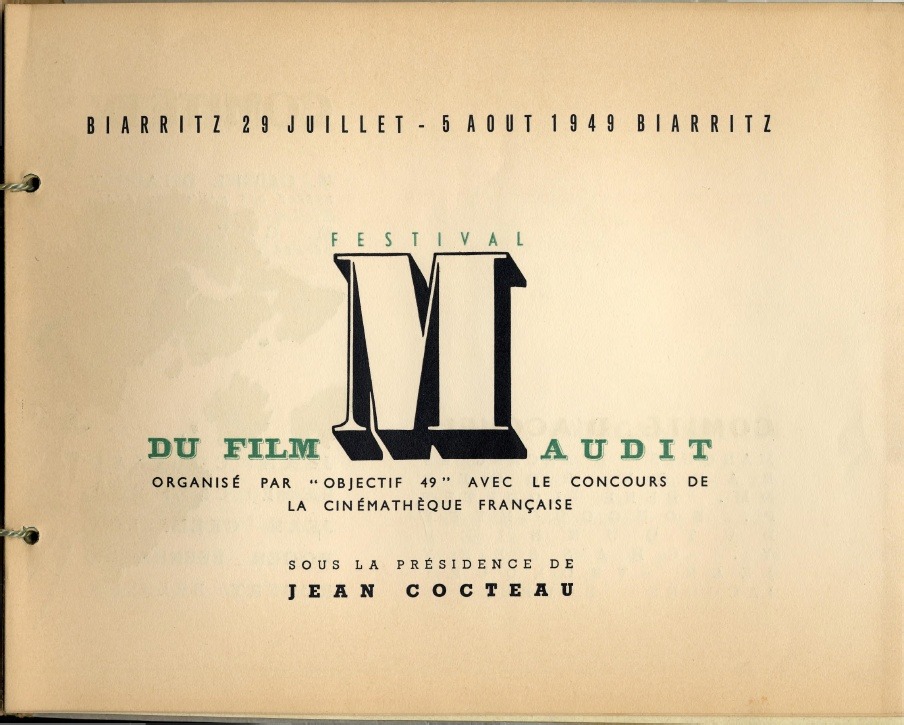

Festival of the Cursed

Festival du Film Maudit Catalogue, 1949, via caboose

''The time has come to honour the masterpieces of film art which have been buried alive, and to sound the alarm. Cinema must free itself from slavery just like the many courageous people who are currently striving to achieve their freedom. Art which is inaccessible to young people will never be art." (Jean Cocteau, 1949)

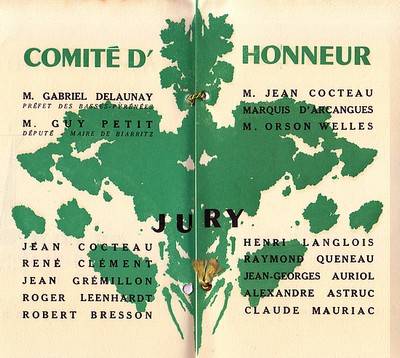

After the end of World War II, the Ciné-club Objectif 49 was founded in Paris. Its members, including Jean Cocteau, Henri Langlois and, as honorary member, Orson Welles, had taken up the cause of propagating a new cinema avant-garde. They were supported by several writers, filmmakers and critics who had joined together under the label Nouvelle Critique, including André Bazin, Raymond Queneau, Jean Grémillon, Alexandre Astruc and Roger Leenhardt. This loosely-bound group planned to stage an independent festival in Biarritz in the summer of 1949; it was to roll out the red carpet for Cinéma maudit, in a nod to Mallarmé's term poètes maudits, the accursed poets.

With this festival, the established representatives of Nouvelle Critique intended to “measure, with purity and frenzy, the current battle lines on the field of cinematographic intelligence and sensibility”. They were also aiming for an exchange of ideas with a group of young cinephiles whose names were known to very few at the time: François Truffaut, Jacques Rivette, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer and Jean Douchet. The announcement of the event, which was to be both urbane and confrontational, was akin to a cult promise: Biarritz would become a test site to roam with one’s accomplices, in order to track down a new spirit in film, which didn't necessarily have to reveal itself only in the current production. What were the films maudits, the accursed films of 1949? Kuhle Wampe by Slatan Dudow, Lumière d'été by Jean Grémillon,Fireworks by Kenneth Anger, films by Jean Renoir, Clifford Odets, Jean Rouch, John Ford and Helmut Käutner, Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne by Robert Bresson, Ride the Pink Horse by Robert Montgomery and L'Atalante by Jean Vigo, plus ten additional films. Many of these have long since become indisputable standard works in film history.

The festival took place in the luxurious venue of the Casino on the Atlantic coast from July 29 to August 5. A doorman politely checked all guests and detained or turned away those who didn’t belong or were improperly attired. Some who clearly didn’t belong were Rivette, Godard, and Truffaut. All under twenty years old, ‘bohemian’, and vociferous, they started a scene with the doorman until the timely arrival of Cocteau, dressed in tails. He shepherded his young friends in with a wave of his hand and, as president of the festival, succeeded in holding together, or at least at a safe distance, the aristocracy on one hand and the young Turks on the other.” (Dudley Andrew) via filmmuseum

Monday, October 8, 2012

X-Ray Vision

A lovely find from the BFI, also known as 'The X-Ray Fiend', this comedy by G.A. Smith combines two very recent innovations: Wilhelm Roentgen's discovery of X-rays in 1895, and Georges Méliès' realisation of the special-effects potential of the jump-cut in 1896. The couple is played by the Brighton comedian Tom Green and Smith's wife Laura Bayley. I like the way the x-ray even turns the woman's umbrella skeletal. That's attention to detail right there.

Labels:

BFI,

Early Cinema,

G.A. Smith,

Silent,

X-Rays

Sunday, October 7, 2012

A Trip To The Moon (1902)

Georges Melies' place in the history of early cinema is secure, of course, as a pioneer of clever trick photography. But he's not really considered a filmmaker as such, a key innovator of film technique. He's more a curiosity, a novelty unto himself. And sure, that camera is resolutely static in all his films, plonked in the stalls like the faithful audience in a Parisienne theatre, but that doesn't mean his mise en scene was primitive. The story of early cinema is usually seen as one of growing narrative sophistication, progress through editing and montage, an evolving visual grammer allowing greater complexity of storytelling. Which is true but has the unfortunate side-effect of marginalising or undervaluing those who don't fit this arc. Melies brought his own talents, obsessions and experience to the medium in the same way Orson Welles utilised radio techniques in Citizen Kane. Melies teeming, inexhaustible imagination, his trickster delight in creating wonder in an audience is the well-spring of cinema every bit as much as Edwin S. Porter's parallel editing in The Great Train Robbery (1903). When the frame is this filled with business, with perspective-stylised scenery, with clever tricks and visual jokes, it seems churlish to ask for movement from the camera too. In this sense he could be seen as a precurser of fellow Frenchman Jacques Tati who similarly loved to fill the static frame with off-centre comic business. (Melies was assuredly comic. Those doddery old scientists with their funny walks and pratfalls have a pantomime charm to them). And yet there is movement of sorts. Check out those dissolves as we travel from earth towards the moon, first seen as a distant orb, then closer with vaguely face-like shadows, and finally that iconic moon-face about to be assaulted by the incoming rocket. There are earlier dissolves too, from the astronomical meeting to the workers making the rocket. But even so, the film doesn't need to justify itself in these terms. The imagination makes the real possible, it's the crucible of the future. Without Melies or HG Wells there wouldn't have been any Neil Armstrong. Which isn't to say he was just a bag of tricks, this is still a narrative film, a story told with breezy economy and impish invention.

Building Up & Demolishing the Star Theatre

'A photograph is not only an image (as a painting is an image) an interpretation of the real; it is also a trace, something directly stencilled off the real, like a footprint or a death mask'

- Susan Sontag, On Photography

In the 21st century we take it for granted that images exist, that we can just record the world around us at will. We've long since lost contact with the spooky magic of this, the unlikely fact that hidden in the chemical world was a process that could capture likenesses, snatch moments out of the flow of time. Do any of us really know how this works? Why it works? Even stranger, that waiting within us all this time was a process called persistence of vision, holding after-images for a fraction of a second on the retina like it knew all along that cinema was coming, that one day we would create our own parallel universe. We hardly think about these things now, or even feel the faintest tremor of dislocation as we move through an image-saturated world, a matrix of visual stimuli from phones, laptops, televisions, internet pages, games consoles, etc. But maybe we should. Maybe we should watch Frederick S. Armitage's pioneering short Building Up and Demolishing the Star Theatre, made in 1901, to give us an inkling of the strangeness we've forgotten. It consists of time-lapse footage of the demolition of the Star Theater at Thirteenth Street and Broadway in New York, filmed from the Biograph Studios office across the street, with exposures taken every four minutes during the course of the thirty day demolition. It was then reversed to create the building-up effect. Theaters were given the option of setting the film order to either Demolish then Build Up or, as in the version above, Build Up then Demolish. Time-lapse is nothing new to any of us, and films like this are ten-a-penny, but this is the first known example and it maintains an eerie air of first disovery, a trace of what it must have been like to see it then, the sheer unprecedented sorcery of it. In the process it brings us back to that sense of wonder, the implications for who we are implicit in the medium, for what we are, what film is, what it does to time, what it tells us about time. The people walking by in the film are dead, yet there they are, caught in a loop of time, forever alive on this day. In this sense, the film is a portal into 1901, into that corner of New York, at Thirteenth Street and Broadway. Except they're walking backwards, the traffic travelling in reverse. It's a premonition. Something strange is about to happen. And then it does, time speeds up. A whirlwind descends on the empty lot across the street and a building starts to take shape, rising out of the ground like an apparition, window arches and connective walls forming through dark pulsating patches of scratchy film-stock, sudden waves of sunlight peeling backwards like a restorative wash. In no time the Star Theatre stands on the corner in all its glory. Calm is restored, but only briefly. The whirlwind descends again. Now the imposing building begins to disappear, whittled away like ants devouring a piece of food. To the left the windows and canopy of the Biograph building flutter in and out, shadows pass through like ominous waves, the traffic a blur, see-through, ghostly. And then it's gone as if it had never been there. The scene reverts to real time, people walk by normally, traffic passes as it should, as if nothing has happened. But it has. We've been shown our place in the universe. Time has been atomised. At this very moment, 1901, Albert Einstein is sitting in a Swiss patent office, surrounded by clocks, formulating his ideas on relativity. Time speeds up and slows down. In fact it bends, dilates, contracts depending on where we are and how fast we're going. Velocity changes time. He's going to write a whole paper on it, his special theory of relativity. With Building Up and Demolishing the Star Theatre Frederick Armitage had beaten him to it. If film was directly stencilled off the real, if it was part of us in some mysterious way, then what happened to it should also happen to us. If film can be sped up, slowed down, reversed, then so can we. Cinema was already proving it. Science just needed to find the mathematics.

Friday, August 31, 2012

Kubrick // One-Point Perspective from kogonada on Vimeo.

Excellent compendium of similar one-point perspective shots in Kubrick films edited to Lux Aeterna by Clint Mansell.

Excellent compendium of similar one-point perspective shots in Kubrick films edited to Lux Aeterna by Clint Mansell.

Wednesday, July 4, 2012

Classic Scene #36

The undoubted highlight of West Side Story, Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim's America is not only one of the most thrilling song and dance routines in cinema history it's also a better critique of the American immigrant experience than a library-full of academic tomes or well-meaning documentaries. 'Skyscrapers bloom in America, cadillacs zoom in America, industry boom in America, twelve in a room in America.' Beneath the fun it's scathingly sardonic, a switchblade cutting through the platitudes of the American Dream, capturing the giddy schizophrenia of the place, hypocrisy and hope locked in a perpetual dance. And yet, the sheer vitality of the music is like a metaphor, something thrillingly American born out of immigrant anger and desire, metabolised from it, people released from backwards lethergy, from stifling convention or political oppression, channelling, at last, all their wit and talent, their teeming energy, into this new place, capitalism's engine room.

Monday, July 2, 2012

Night Train To Munich (1940)

Carol Reed's Night Train To Munich is a very enjoyable film in the mold of Hitchcock's The Lady Vanishes but lacking that little something that proves why Hitchcock is a genius and Reed only a very good director. Nevertheless, the sense of hokum being made from yesterday's headlines is infectious. It begins with the Germans marching into Prague, forcing armour-plating scientist Dr Bomasch to flee to England leaving his daughter Anna (Margaret Lockwood) behind. She's arrested and sent to a camp but escapes with the aid of sympathetic Czech prisoner Karl Marsen (the always excellent Paul Henreid) and makes her way to England. However the Gestapo kidnap them back and British agent Dickie Randall (Rex Harrison) is despatched to follow them disguised as a German officer. It's as if Lady Vanishes writers Sydney Gilliat and Frank Launder decided to prove they didn't need Hitchcock now that he'd high-tailed it to America. And they do prove it. The film is fun and engrossing with good early detail of British seaside attractions and Nazi concentration camps. Admittedly Lockwood isn't as sexy as she was in the earlier film, Caldicott and Charters (Naunton Wayne and Basil Radford) are slightly less fun (as befits the fact that war has broken out since 1938) and Harrison is ridiculous as a Nazi officer but it doesn't matter, everyone is appealing and it rattles along to an exciting cable-car shoot-out finale. You do feel, though, that Hitchcock would've made slightly more of that, found a striking camera angle, had someone fall to their death. His big-bellied shadow hovers over proceedings which is a little unfair but it's so nearly a Hitchcock film it's hard not to look for that extra something that made him better than the rest; a greater eye for composition, a deeper instinct for mise-en-scene, a more piercing attitude to sex. You always feel Hitchcock has some inner compulsion at stake in his films as well as being a keen pupil of technique and its effect on audiences. Is this true of Reed? Why is he making this film? Isn't it Hitchcock-lite, just as The Third Man was Welles-lite? I don't mean to disparage Reed, he's done a fine job here and three or four of his later films are classics but it's hard to sense a unified intelligence behind his work, just as it's hard to imagine Hitchcock ending up making a faceless musical like Oliver! (Pauses. Thinks about the notion of a Hitchcock musical. Ignores the little-seen Walzes From Vienna (1934) because it was before Hitchcock had truly found his voice. A proper in-his-prime musical. What would that have been like? What if, just as he responded to Michael Powell's Peeping Tom with Psycho, he'd responded to Powell's The Red Shoes? What would a Hitchcock musical look like? Sweeney Todd maybe? How much better would that have been with Hitchcock instead of that tedious child Burton?) None of which should take away from the fact that Night Train To Munich is a frequently tense, amusing, well-written adventure with just enough from-the-headlines urgency and grit to keep it from silliness.

Saturday, May 12, 2012

Film Club Reviews #15

I've been trying to pinpoint where Cary Fukunaga's adaptation of Jane Eyre goes wrong. It's handsomely made with fine location work and composition of shots, the performances are all strong and it's properly cinematic. Upon reflection I think the screenplay is the problem. There's too much to get in. Screenwriter Moira Buffini's decision to start at a moment of dramatic crisis late in the book and flashback to Jane's childhood is a good one but by the end too many plot developments are left to get through in too short a time. It feels rushed, a cascade of improbable incident. Which is a pity because there's much to admire here. Mia Wasikowska is compelling as Jane, a study of inner strength, restraint and vulnerability, one of those performances that are all presence, the camera in thrall to her face. Michael Fassbender has presence to burn in any role but give him Victorian sideburns, riding breeches and a scowl and you're guarenteed the business. His Rochester is less gothically mysterious than the book, more distracted, burdened, a man made remote by the secrets he has to keep. Judi Dench is reliably kindly and humourous as Mrs. Fairfax and there's fine support too from Sally Hawkins as nasty Mrs. Reed and Amelia Clarkson as the young Jane. Add a great feel for landscape and you have a film well worth seeing despite the rushed later stages. I should add I was the only one who seemed to have a problem with it. Everyone else loved it.

Friday, May 11, 2012

Film Club Review #14

When is a documentary not a documentary? When it's made by Werner Herzog of course. There were rumblings of complaint after we screened Cave Of Forgotten Dreams from some members frustrated with its refusal to lay out all the facts in proper documentary style and thrown by its left-turn ending. The thing is, Herzog isn't a documentary-maker as such, he's more interested in the metaphyics than the facts, and the film should be seen as a meditation on what the caves might mean and the kinds of people they attract. The caves in question being the Chauvet caves in Southern France, home to the oldest known pictorial creations of mankind. As the public are unlikely to ever be allowed inside the caves Herzog's film is an invaluable record of the wonders they hold. It was truly spellbinding to see these drawings of horses, bison, lions and rhinos emerge out of the darkness or a human handprint from thousands of years ago, emblematic of human consciousness, the awakening of self awareness and the transformative power of art. Some members felt because we couldn't show it in 3D we shouldn’t have shown it at all, but really, it didn’t need that. If your imagination can’t process the wonder without the aid of visual Viagra then I’m sad for you. As usual Herzog found odd characters, coaxed revelatory admissions from people, and arrived at a conclusion involving albino alligators that was too much for some. A nearby nuclear power plant has raised the temperature of the local environment and caused evolutionary change in these alligators. This is the same, Herzog seems to say, as what happened in the caves, mankind made an evolutionary step forward, a mutation of consciousness, due to changes in the environment. Whether you buy this or not, there's no denying the experience of the caves, the sense of time as both impossibly distant and mysterious and yet also immediate and alive because of the way Herzog brings us close to the paintings and they bring us close to the people who made them.

Thursday, May 10, 2012

Film Club Review #13

How to explain the anomaly that is Midnight in Paris? Because lets be honest here, Allen has been in severe decline for over a decade now. The last two of his films I’ve seen where Match Point and Vicky Christina Barcelona, the former a travesty the latter mildly diverting but lightweight and forgettable. (And the trailer for To Rome With Love makes it look heart-sinkingly bad). And yet, here this is, a gem, a throwback to Allen’s heyday, a film that could have been made in the 1980s, sandwiched between The Purple Rose of Cairo and Radio Days. Sure it's cozy and soft-focused and doesn't engage with reality very much but none of that matters. The fantasy prevails. Owen Wilson was born to be an Allen surrogate and Adrian Brody’s Dali is arguably the best five minutes of his entire career. The message of the film, that every generation romantisises previous times, that these 'golden ages' almost certainly didn't feel special to the people living them, yearning as they were for their own idealised pasts, is undermined by the experience of the film itself. Paris of the 20s does seem golden here, an endless party, a moveable feast, full of larger-than-life characters and mysterious muses, a young man's dream of artistic nirvana revisited. It glows with sweet wonder.

Labels:

film club reviews,

Midnight in Paris,

Woody Allen

Wednesday, May 9, 2012

Film Club Reviews #12

I rewatched M last year, Mark M For Murder, and was so struck by how modern it still seemed, not just thematically but visually as a thriller, I decided it would be perfect to show at the film club. And I was right. To see it on the big screen was a revelation. Watching it the way it was intended to be seen intensified its effect tenfold. It traps an audience as inexorably as the mob closes in on Hans Becker. There's nowhere to escape. A classic not embalmed in another time or place but still a live issue, a cinematic time-bomb.

Labels:

film club reviews,

Fritz Lang,

M,

Peter Lorre

Tuesday, May 8, 2012

Film Club Reviews #11

Is it possible to wipe the slate clean and start again, no matter how old you are or how many mistakes you've made. That's the question at the heart of Mike Mills' hopeful, bittersweet Beginners. Are we trapped by convention, age, sexuality, family history? When Oliver Fields' mother dies his father Hal shocks him by revealing his homosexuality. What follows is an education in tolerance and empathy. In the years left before he gets cancer Hal lives a life of freedom, true to himself at last, grabbing what happiness he can. It's an example his son struggles to follow. He meets Anna, a French actress, and embarks on a sweet if fraught relationship with her. It's funny, sad, slightly bewildered, people sabotaging their lives to avoid getting hurt. Nothing is easy for them. Mills fully understands the failure they're capable of, the emotional cages they've locked themselves into. Darkness is ready to flood in at any time. But the film's lightness of touch carries us through. It's visually witty, using Oliver's job as a graphic artist to break up the structure, give it narrative energy. This is how Oliver sees the world, looping memory, subtitled dogs, history as a series of rapid-fire montages. If it's undermined in places by hazy, liberal niceness and romantic scenes that flirt with tweeness, it gets away with it thanks to shaggy-dog charm and a seam of melancholy that runs through it like a grace note. Ewen McGregor's Oliver is a hurt child in a man's body, Christopher Plummer has the good grace to underplay a sure-fire Oscar role and Melanie Laurent's radiance carries Anna beyond the implausible. There are also brief flashbacks to childhood afternoons Oliver spent with his mother, Georgia, (Mary Page Keller) that are arguably the most effective and memorable in the film. So much hinted at, so much unsaid about a clearly talented woman going crazy with boredom, someone who didn't get a second chance.

Monday, May 7, 2012

Mystic River

For those of you who love this film as much as I do just thought I'd mention that my review of Jean Vigo's timeless classic L'Atalante can be read over at arts and pop culture magazine Oomska

Film Club Reviews #10

Terrific exploration of masculinity from Susanne Bier, the modern mistress of emotional filmmaking, the 21st century Nicholas Ray. Her films are about love in all its complicated shades, the devastation it can cause, how uncontrollable it is, how it can lead us into dangerous territory. In A Better World starts with Anton, a doctor working at a refugee camp in a dangerous African country where gangs mutilate girls and justice doesn't exist. Back home in civilised Denmark his marriage to Marianne is heading for divorce. They have two young sons, the eldest of which, ten-year-old Elias, is being bullied at school. Or he is until Christian, a new boy, defends him by threatening the bully with a knife. Christian's mother has died of cancer and he's a powderkeg of unresolved grief and resentment. When Anton stops a fight involving his younger son, the other father, a mechanic, slaps him in the face. Later he visits this man, with Elias and Christian, to show them he's not afraid. But the mechanic slaps him again, Anton refusing to respond, determined to prove he's the better man for rising above violence. But the children don't see it this way. Christian persuades Elias that if his father won't do something about this bully it's up to them to enact revenge. And so things escalate. Along the way the plot resolves itself in a somewhat contived fashion but the emotional journey earns it. These are children, after all, perilously close to destruction, and we should want them to survive. Bier and her regular screenwriter Anders Thomas Jensen delight in taking soap opera plots and infusing them with authentic detail. It's a tightrope walk that doesn't always work but when it does the result is vivid and engrossing filmmaking that asks questions of us few films get close to. How do we respond when our children suffer bullying and look to us for protection, for schoolyard justice? How do men deal with violence in a civilised society, the violence they're confronted by and the violence inside themselves? What is justice without retribution? How can we defend ourselves without descending to the level of our attackers? This is acutely observed cinema, filmed with big-budget panache and impossible not to be moved by if you’re a parent, a father especially.

Labels:

film club reviews,

In A Better World,

Susanne Bier

Film Club Review #9

Based on the ''beloved'' bestseller, Mona Achache's The Hedgehog portrays the lonely existence of Renée, a middle-aged, dowdy concierge in a well-to-do Parisian apartment building and Paloma, the daughter of a wealthy family in the same building who records her life with a video camera and plans to kill herself on her twelfth birthday. In their own ways they've both stopped believing in life. Then mysterious new tenant Mr. Ozu arrives and they begin to see things differently. Ironically, for a film that's all about hidden depth The Hedgehog has all the intellectual riguor of a mind/body/spirit bestseller, full of thumpingly obvious symbolism, never really engaged with existential crisis, happy instead to set it up to be skittled by the power of love or the easy uplift of a good old cry. Togo Igawa does wonders with that cardboard paragon of Eastern virtue Mr Ozu, almost making him a flesh and blood character and Josiane Balasko is excellent as Renee, her wary, deadpan expression gradually revealing the sweet woman hidden beneath the grouchy exterior. Life is worth living, the film tells us, if you open yourself up to it, reveal the real you hidden inside. Which is fine, of course, but does it have to be made explicit by a secret room of books that constitute Renee’s true personality, a room with a door that’s always closed. Just like her heart. She’s a hedgehog, y'see, prickly on the outside, but inside ‘she’s as refined as that falsely lethargic, staunchly private, and terribly elegant creature’. (This from the mouth of an eleven-year-old). Appearances can be deceiving then. Like this film which prides itself on being philosophical, references the great art of Tolstoy and Yasujiro Ozu, but underneath the elegant surface it's just soft-headed trash dressed up in arty clothes, a so sad but so lovely experience for educated sentimentalists.

Sunday, April 8, 2012

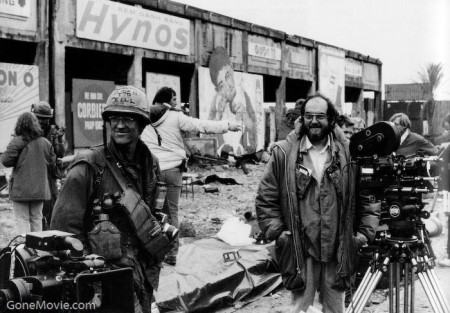

Full Metal Boxes

I was musing yesterday about how Jon Ronson's article on being allowed access to Stanley Kubrick's estate after his death would make a good basis for a film, and actually Ronson did turn it into a documentary in 2008 called Stanley Kubrick's Boxes. Here's a clip about how he found some old film cans in a stable that turned out to be eighteen hours of footage Kubrick's daughter shot on the set of Full Metal Jacket. We then see some of this footage, arguing over tea breaks, setting up and filming scenes, moments picked I think to show Kubrick as calm, practical and amused, in order to counteract the claim he was becoming increasingly unhinged at this time. Although, personally, I'd like to believe he really did eat all three courses of his dinner simultaneously in the manner of Napoleon.

Saturday, April 7, 2012

Operation Snafu

Been suffering one of my occassional non-verbal phases, a writer's block that gets worse as new ideas pile up on top of already unfinished or unstarted ones. As befits an epic dumb-show of this nature, I've taken to the visual therapy of Tumblr to keep sanity and momentum going. Anyway, in order to try getting out of this snafu, I've decided to do a ragbag post of recent film-related stuff.

Firstly there's this excellent article from 2004 by Jon Ronson called Citizen Kubrick about how he was invited to Stanley Kubrick's estate after his death and allowed roam through his archive of boxes. It's fascinating, makes you wish it was still there so you could go too. There's also a sense, as the Citizen Kane reference implies, that there's more here than simply a newspaper article; there's a short story, novel or film asking to be made, an exploration of a man's life, of cinema and obsession, through the immaculately-catalogued debris of his life. A kind of Krapp's Last Tape, maybe, except with boxes, personally designed, with easy-to-remove tops.

Another insight into a master director's work came from Jeff Desom, who atomised Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window and then put it back together as a panoromic view of the film's famous courtyard. Originally a 20-minute loop, here it's been condensed into a three-minute timelapse. For an explanation of how it was made go here and for an interview with its maker here.

Sometimes not living in a city sucks, especially when it comes to film screenings. Like, for instance, London's Future Cinema, who are showing an interactive screening of Bugsy Malone where the audience get to dress up as gangsters and flappers in a mock-up of the film's Prohibition speakeasy, Fat Sam's, with the whole thing ending in a real custard pie fight. Looks like great fun.

Firstly there's this excellent article from 2004 by Jon Ronson called Citizen Kubrick about how he was invited to Stanley Kubrick's estate after his death and allowed roam through his archive of boxes. It's fascinating, makes you wish it was still there so you could go too. There's also a sense, as the Citizen Kane reference implies, that there's more here than simply a newspaper article; there's a short story, novel or film asking to be made, an exploration of a man's life, of cinema and obsession, through the immaculately-catalogued debris of his life. A kind of Krapp's Last Tape, maybe, except with boxes, personally designed, with easy-to-remove tops.

Another insight into a master director's work came from Jeff Desom, who atomised Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window and then put it back together as a panoromic view of the film's famous courtyard. Originally a 20-minute loop, here it's been condensed into a three-minute timelapse. For an explanation of how it was made go here and for an interview with its maker here.

Sometimes not living in a city sucks, especially when it comes to film screenings. Like, for instance, London's Future Cinema, who are showing an interactive screening of Bugsy Malone where the audience get to dress up as gangsters and flappers in a mock-up of the film's Prohibition speakeasy, Fat Sam's, with the whole thing ending in a real custard pie fight. Looks like great fun.

Labels:

Bugsy Malone,

hitchcock,

Jon Ronson,

kubrick,

Operation Snafu,

Rear Window

Wednesday, February 8, 2012

Classic Scene #35

Arguably the greatest opening scene of any film, Squadron Leader Peter Carter (David Niven) redefines gentlemanly bravery in the face of impending death in Powell and Pressburger's A Matter of Life and Death. It's a little movie unto itself. Carter is heartbreaking, facing his fate with stoic good humour, quoting Walter Raleigh's The Pilgrimage and Andrew Marvell's To his Coy Mistress. He's an ideal of a certain kind of Englishness, of gentlemanly values, a chivalric echo. Throughout the war years in films like A Canterbury Tale and The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, Powell was preoccupied with this English tradition, and here he gives us it's epitome in Peter Carter. Niven is fantastic but let's not underestimate what Kim Hunter brings to the scene. Her reactions are just as important to the connection they make. She provides American vitality and youth, the grave empathy of her peaches and cream complexion and not incidentally, all the information Peter needs to dream the rest of the film. And finally there's the technicolour which is like no other, a gorgeous burnished glow that's like life itself as seen for the last time.

Saturday, February 4, 2012

Hitchcock/Truffaut

Over twenty-five years ago (don't want to think too much about how long ago that was) a friend of mine went to America on holiday, still a reasonably exotic thing to do in those days, the mid 1980s. When he returned I called to his house to hear all about it and discovered that he'd brought me back a present, a book, this book.

Truffaut had died in October 1984 so looking back now it was probably why the book was in the shops and caught his attention. I have to admit I had no idea Truffaut was dead. I was still in the early days of my film education and huge swaths of cinema were a mystery to me (not to mention what it was like to live in a cultural backwater with no internet or anything else to keep you up to speed with things like the deaths of European film directors.) Hitchcock, on the other hand, was already an obsession. I still have the book and dip into it every now and again. Here is a clip from a interview Truffaut did in April 1984, his last TV appearance, on the show Apostrophe, in which he discusses the book and Hitchcock in general with host Bernard Pivot and fellow guest Roman Polanski.

Truffaut had died in October 1984 so looking back now it was probably why the book was in the shops and caught his attention. I have to admit I had no idea Truffaut was dead. I was still in the early days of my film education and huge swaths of cinema were a mystery to me (not to mention what it was like to live in a cultural backwater with no internet or anything else to keep you up to speed with things like the deaths of European film directors.) Hitchcock, on the other hand, was already an obsession. I still have the book and dip into it every now and again. Here is a clip from a interview Truffaut did in April 1984, his last TV appearance, on the show Apostrophe, in which he discusses the book and Hitchcock in general with host Bernard Pivot and fellow guest Roman Polanski.

Tuesday, January 31, 2012

Classic Scene #34

Marilyn Monroe performs One Silver Dollar from River of No Return. What a fantastic singer she was. I don't mean her voice as such, although it was fine, but her immersion in a song's meaning and emotion. It's where her acting is at its finest. While she was a peerless light comedian, her serious acting could be clunky at times (although by no means always) but just watch her sing. 'Love is a shining dollar/Bright as a church bell's chime/Gambled and spent and wasted/And lost in a dawn of time'. You feel she understands this song completely. Even the camera cutting away to follow Mitchum through the crowd can't break the spell.

Labels:

classic scenes,

Marilyn Monroe,

River of No Return

Monday, January 16, 2012

Alternative Universe Films

Just came across this. Someone wondered what stars of yesteryear would be cast in todays films (and who would direct them) and decided to create posters for these films. It's very good. The casting is spot on. Warren Oates as Jesus in Lebowski made me shout yes! at the computer. How about Trainspotting by Godard? Or Rushmore as a Nicholas Ray film with James Dean, James Stewart and Audrey Hepburn. Fritz Lang's 2001 anyone? It's inspired. Honestly, I would kill to see some of these Movies from An Alternative Universe.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)