The famous dance scene from Godard's Bande a Part (1964), has a lovely spontaneous feel to it, a found moment, choreographed magic entering ordinary life, like none of them had any idea they were going to do it until suddenly they were, transported by the music into synchronised grace. 'Franz thinks of everything and nothing,' the narrator tells us, 'uncertain if reality is becoming dream, or dream reality.'

Twenty-eight years later Hal Hartley re-enacted the scene in Simple Men (1992). In the original the music was an R&B number composed for the film by Michel Legrand and christened the Madison dance by the actors. Here the jukebox is playing Kool Thing by Sonic Youth.

This dance is less ineffably cool than the Godard, perhaps, more shambolically awkward, more contrived in the way anything that's a copy rather than the original will inevitably be, but this makes it its own thing, I think, an outburst of defiant energy and noise in a dead-ass country town. One's magic, the other's release. What both scenes have in common, though, is the way the men seem to take their cue from the women. Their un-selfconscious spontaneity seems to create a space, a moment, where dream and reality can meet.

There's something almost religious about this, an age-old connection between dance and altered states. Consider the word dervish. It means doorway to god or enlightenment. The dervish dancers of the Sufi religion whirl incessantly while repeating the name of god until they fall into a trance, a state of deep worship. Surely there's a fragment of this idea in these scenes, the trance state of music and dance taking them towards a more modern state of enlightenment, a place where they feel intensely alive but also blessed by something greater than themselves, something not of this world.

Friday, May 28, 2010

Wednesday, May 26, 2010

The Kino Eye

A film is never really any good unless the camera is an eye in the head of a poet

Pupil, from the Latin pupilla, 'a little doll'. When the Romans looked into one another's eyes they saw a doll-like reflection of themselves. The old Hebrew expression for pupil is similar: eshon ayin, which means 'little man of the eye'

To me, one of the cardinal sins for a scriptwriter, when he runs into some difficulty, is to say ‘We can cover that by a line of dialogue.’ Dialogue should simply be a sound among sounds, just something that comes out of the mouths of people whose eyes tell the story in visual terms.

There are many explanations for what inspired the legend of the Cyclopes - the one-eyed monsters of classical mythology - invoking everything from an ancient find of mysterious dwarf elephant skulls, to the blacksmith's habit, in the days before protective goggles, of protecting one eye with a patch. But the most likely inspiration is also the saddest; occasionally a human cyclops survives in the womb long enough to emerge visibly disfigured. Once upon a time, someone got a good look at what they had aborted - and for ever after wished they hadn't

In the early 50s two research teams stumbled independently on a way to stabilise images on the retina. They fastened tiny spotlights to the contact lenses their volunteers wore. It didn't matter how much the volunteers moved their eyes: the little spots of light would always be stabilised at exactly the same places on the retinas. The results could not have been more spectacular: after about a second of this curious, frozen vision, the volunteers lost sight of the lights. The eye exists to detect movement. Any image, perfectly stabilised on the retina, vanishes. Our eyes cannot see stationary objects, and must tremble constantly to bring them into view.

Dr. Mabuse is a master of disguise like Fantômas and a master of telepathic hypnosis, not unlike the hypnotist Dr. Caligari. Like Fu Manchu, Mabuse commits very few of his crimes in person, instead operating primarily through a network of agents acting out schemes he has laid down for them. Mabuse's agents range from career criminals following him for money, to innocents blackmailed or hypnotized into cooperation, to dupes so successfully manipulated they do not realize that they are doing exactly what Mabuse planned for them to do

Both Peeping Tom and Vertigo preface their narratives with the extreme close-up of an eye, as if to announce at once the themes of vision and subjectivity. In Peeping Tom we can detect, below the closed lid, the rapid eye movement that denotes dreaming; the eye thereupon opens wide, introducing a story that has the intensity and condensed logic of dream, or nightmare

As Vertigo's credits begin, the camera moves across the face of an unidentified woman. After first framing the mouth, it moves up to a close-up of the right eye, which opens wide, as if in shock; then moves further in, as if into its interior depths, from which galaxy-like spirals emerge.

Our eyes see very little and very badly – so people dreamed up the microscope to let them see invisible phenomena; they invented the telescope…now they have perfected the cinecamera to penetrate more deeply into he visible world, to explore and record visual phenomena so that what is happening now, which will have to be taken account of in the future, is not forgotten.

No one knows how we focus our attention. No one even knows how to ask the right questions. If the eye is an outpost of the brain, it is - by the same logic - an incursion of the light. When our eyes are drawn to a change in the scene, what draws them: our desire to see, or the change in the scene? Is one a cause, the other an effect? Or - in Goethe's memorable phrase - do 'the two together constitute the indissoluble phenomenon'?

Stand about eight to ten inches from a mirror and look at your left eye. Now look at your right eye, and then back at your left eye. Do this five or six times in quick succession. You will not notice any movement - your eyes will seem to be completely still. But this is in fact not the case, as an observant friend will immediately tell you: your eyes move quite a lot with each shift of focus. The blurred swish during the movement of the eye is somehow snipped from our conscious awareness, and we are left with just the significant images before and after the movement. Not only do we not see the blurred movement, we are unaware that anything has been removed. And this is happening all the time: with every movement of our eyes, an invisible editor is at work, cutting out the bad bits before we can even see them

I am eye. I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, am showing you a world, the likes of which only I can see.

In 1875 the Viennese physiologist Sigmund Exner showed that two brief, stationary flashes, provided they are not too far away from each other, are seen as a single object in motion. This habit of fusing stationary dots into moving objects makes a great deal of sense in nature, where prey and predators disappear and reappear constantly as they move through grass, run behind trees, and peer around rocks. But the power of the phenomenon (called the phi phenomenon) will perhaps best be demonstrated the moment you turn on the television. Every film and TV programme ever made depends on phi. Both display still images quickly enough for our eyes to read them as a single moving image.

Perhaps our eyes are merely a blank film which is taken from us after our deaths to be developed elsewhere and screened as our life story in some infernal cinema

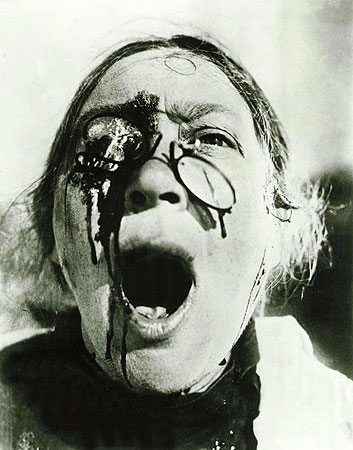

Images: Orson Welles, Pan's Labyrinth, Psycho, Clash Of The Titans, Repulsion, Dr Mabuse The Gambler, Peeping Tom, Vertigo, The Crawling Eye, Grandma's Reading Glasses, Un Chien Andalou, The Man With The Movie Camera, The Battleship Potemkin, A Clockwork Orange

Quotes: Orson Welles, A Natural History of the Senses by Diane Ackerman, Alfred Hitchcock, The Eye: A Natural History by Simon Ings, The Eye: A Natural History, Dr Mabuse Wikipedia page, Vertigo (BFI Film Classics) by Charles Barr, Dziga Vertov, The Eye: A Natural History, The Conversations: Walter Murch And The Art Of Editing Film by Michael Ondaatje, Dziga Vertov, The Eye: A Natural History, Jean Baudrillard

Monday, May 24, 2010

Classic Scenes #9

'And two hard boiled eggs...'

Labels:

classic scenes,

marx brothers,

night at the opera

Saturday, May 22, 2010

The Killer Elite

Cinema is, as we all know, the stuff that dreams are made of, all our romantic reveries and adventurous daydreams come to life, a projection of the perfect world we'd ideally love to be living in, full of excitement and happy endings. Or it would be if it wasn't for one little problem: not all our dreams are so wholesome. In fact some are downright dark and scary. And nothing can get at the malign impulses that lurk in our subconscious quite like cinema. It's something filmmakers have known since the earliest days, audiences love the vicarious thrill of illicit acts just as much as wholesome ones.

Which brings us to the horror and fascination we have with those who disobey the most serious of all the Ten Commandments. As Ernest Hemingway once observed, ''when a man is still in rebellion against death he has pleasure in taking to himself one of the Godlike attributes, that of giving it. This is one of the most profound feelings in those men who enjoy killing.'' What he neglected to mention was the pleasure an audience often experiences, whether it's in the bullring or the omniplex, while watching this rebellion against death. It's a primeval experience, a ritualistic act, one that connects cinema to ancient rites and religious transfiguration. The cinematic killer enacts our hidden desire to kill and our hidden relief that the victim is someone else. They die for us, so we don't have to. They kill for us, so we don't have to.

So whether it's the serial killer, the vigilante or the hitman, the killer is always with us, haunting our dreams, charming our worst instincts, hunting us down with remorseless determination. With Michael Winterbottom's The Killer Inside Me set to be the latest profile of one of cinema's most troubling and enduring residents, it's time to look back on five of the more memorable ones.

1. Speaking of Hemingway, his famous short-story The Killers was the basis for one of the great film noirs of the 1940s. Two hitmen arrive in a small town to kill someone called 'the Swede'. They wait in a diner for him to arrive. The film goes on to expand on this simple set-up, giving us the back story as to why the Swede has ended up here, (it's all a girl's fault wouldn'tcha know) but it starts with a faithful recreation of the original story in all its noirish menace.

2. We can't talk killers, of course, without talking Hitchcock. Killers were one of specialities and I could easily pick five clips from his films alone. In the end I choose Bruno Anthony from Strangers On A Train. It's in incomparable performance from Robert Walker, the killer as psychopath, victim and charmer all in one. Hitchcock was always trying to implicate us in his murderous schemes, manipulating us to identify with killers, and here as Bruno murders the woman at the carnival, Hitch literally lowers her body into our laps, presents her to us as a sacrifical offering.

3. It's hard to imagine the western without killers. The gunslinger, the outlaw and the gun-for-hire were staples of pretty much every western ever made. So an enormous wealth of ornery so-and-sos in black hats to choose from then. I've gone for an Italian take on this most American of genres. Surely few killers have ever had a cooler (or better soundtracked) entrance than blue-eyed Frank in Sergio Leone's Once Upon A Time In The West. The fact that Frank is played by Henry Fonda, that paragon of liberal justice in films like The Grapes of Wrath and Twelve Angry Men only makes it all the better.

4. Not all movie killers are human, of course. Monsters, alien creatures and pissed-off animals have all menaced mankind over the years. Most of these can be explained by the unpredictability of nature or our instinctual fear of the unknown. Movies where we imagine being preyed upon by our own technology, on the other hand, are harder to explain. John Carpenter's Christine (1983) is a good example of this. In Stephen King's original book the car was haunted. In the film, however, it has no discernable reason for turning on humanity. It's just bad and it wants to kill us. Technophobia was clearly in the air. Maybe Christine travelled back from the same future depicted the following year in The Terminator, where all our machines have finally risen up against us?

5. And finally, a more recent phenomenon is the arrival of the female killer. It's been a staple of exploitation movies and comic books for some time of course, but it's been gradually making its way into the mainstream as trash aesthetics and comic book sensibilities have taken over popular culture. It's female empowerment meets geek boy fantasy in an unholy alliance and it surely reached a new zenith this year with Hit Girl's gleeful carnage in the wonderful Kick Ass.

Which brings us to the horror and fascination we have with those who disobey the most serious of all the Ten Commandments. As Ernest Hemingway once observed, ''when a man is still in rebellion against death he has pleasure in taking to himself one of the Godlike attributes, that of giving it. This is one of the most profound feelings in those men who enjoy killing.'' What he neglected to mention was the pleasure an audience often experiences, whether it's in the bullring or the omniplex, while watching this rebellion against death. It's a primeval experience, a ritualistic act, one that connects cinema to ancient rites and religious transfiguration. The cinematic killer enacts our hidden desire to kill and our hidden relief that the victim is someone else. They die for us, so we don't have to. They kill for us, so we don't have to.

So whether it's the serial killer, the vigilante or the hitman, the killer is always with us, haunting our dreams, charming our worst instincts, hunting us down with remorseless determination. With Michael Winterbottom's The Killer Inside Me set to be the latest profile of one of cinema's most troubling and enduring residents, it's time to look back on five of the more memorable ones.

1. Speaking of Hemingway, his famous short-story The Killers was the basis for one of the great film noirs of the 1940s. Two hitmen arrive in a small town to kill someone called 'the Swede'. They wait in a diner for him to arrive. The film goes on to expand on this simple set-up, giving us the back story as to why the Swede has ended up here, (it's all a girl's fault wouldn'tcha know) but it starts with a faithful recreation of the original story in all its noirish menace.

2. We can't talk killers, of course, without talking Hitchcock. Killers were one of specialities and I could easily pick five clips from his films alone. In the end I choose Bruno Anthony from Strangers On A Train. It's in incomparable performance from Robert Walker, the killer as psychopath, victim and charmer all in one. Hitchcock was always trying to implicate us in his murderous schemes, manipulating us to identify with killers, and here as Bruno murders the woman at the carnival, Hitch literally lowers her body into our laps, presents her to us as a sacrifical offering.

3. It's hard to imagine the western without killers. The gunslinger, the outlaw and the gun-for-hire were staples of pretty much every western ever made. So an enormous wealth of ornery so-and-sos in black hats to choose from then. I've gone for an Italian take on this most American of genres. Surely few killers have ever had a cooler (or better soundtracked) entrance than blue-eyed Frank in Sergio Leone's Once Upon A Time In The West. The fact that Frank is played by Henry Fonda, that paragon of liberal justice in films like The Grapes of Wrath and Twelve Angry Men only makes it all the better.

4. Not all movie killers are human, of course. Monsters, alien creatures and pissed-off animals have all menaced mankind over the years. Most of these can be explained by the unpredictability of nature or our instinctual fear of the unknown. Movies where we imagine being preyed upon by our own technology, on the other hand, are harder to explain. John Carpenter's Christine (1983) is a good example of this. In Stephen King's original book the car was haunted. In the film, however, it has no discernable reason for turning on humanity. It's just bad and it wants to kill us. Technophobia was clearly in the air. Maybe Christine travelled back from the same future depicted the following year in The Terminator, where all our machines have finally risen up against us?

5. And finally, a more recent phenomenon is the arrival of the female killer. It's been a staple of exploitation movies and comic books for some time of course, but it's been gradually making its way into the mainstream as trash aesthetics and comic book sensibilities have taken over popular culture. It's female empowerment meets geek boy fantasy in an unholy alliance and it surely reached a new zenith this year with Hit Girl's gleeful carnage in the wonderful Kick Ass.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)