I love Walter Hill's The Warriors , in no small part due to the opening credit sequence. It's a little masterclass in how you can establish location, character, plot and mood all before the film's even started. Everything about it is great: the opening shot of the Coney Island Ferris Wheel, spokes lighting up against the night sky, (all paths metaphorically leading to the centre), the fantastic theme music driving everything forward, graffiti-credits looming out of the darkness, spray-paint red coolly blending with station-light blue against the tunnel blackness, the intercutting of the dialogue scenes with the train speeding towards the city. Honestly, it's almost a pity it has to end, I could quite happily watch a whole film of this, narrative evolving in clipped statements intercut with shots of the train moodily hurtling through the night. By the time it does end, the audience, if they're anything like me, is giddy with anticipation for what's to come. As the man says, 'whole lotta magic.'

Monday, September 27, 2010

Saturday, September 25, 2010

The Film Club Reviews #7

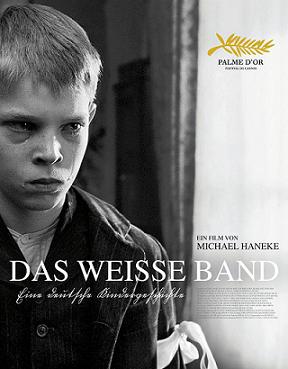

The White Ribbon (2009)

The second film of our winter season was in stark contrast to the first, (feelgood Irish documentary His & Hers). As always with Haneke much is left unsaid or hinted at with mysterious events threatening the status quo of seemingly normal society, in this case, a small village in Northern Germany on the eve of the First World War. Visually and thematically recalling the Scandinavian austerity of Dreyer and Bergman (but with a devastating frankness all its own), it also exudes a mise-en-scène mastery worthy of Hitchcock. And as with Hitchcock, at heart the mystery is a McGuffin, a means to darker moral ends. Haneke isn't interested in who kidnapped the children or burned down the barn, his real concern is in what these events reveal about family life and society at large. We watch religious repression and social conformity incubate violence and intolerance, ordinary youthful vitality and exuberance denounced in the name of idealised goodness. It's not too difficult to imagine these children twenty years later, conditioned by stern authority and desire for purity, voting for a regime promising them both. With stunning black and white photography capturing every child's face in vibrant close-up, faces brimming with confusion, hurt, trust and defiance, The White Ribbon will linger long in the mind.

The second film of our winter season was in stark contrast to the first, (feelgood Irish documentary His & Hers). As always with Haneke much is left unsaid or hinted at with mysterious events threatening the status quo of seemingly normal society, in this case, a small village in Northern Germany on the eve of the First World War. Visually and thematically recalling the Scandinavian austerity of Dreyer and Bergman (but with a devastating frankness all its own), it also exudes a mise-en-scène mastery worthy of Hitchcock. And as with Hitchcock, at heart the mystery is a McGuffin, a means to darker moral ends. Haneke isn't interested in who kidnapped the children or burned down the barn, his real concern is in what these events reveal about family life and society at large. We watch religious repression and social conformity incubate violence and intolerance, ordinary youthful vitality and exuberance denounced in the name of idealised goodness. It's not too difficult to imagine these children twenty years later, conditioned by stern authority and desire for purity, voting for a regime promising them both. With stunning black and white photography capturing every child's face in vibrant close-up, faces brimming with confusion, hurt, trust and defiance, The White Ribbon will linger long in the mind.

Thursday, September 16, 2010

Great Title Sequences #1

We have to start with the grandaddy of all title sequences, the Saul Bass-designed credits for Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo. They're so good, in fact, they have us hooked even before they begin. In the darkness we hear the first strains of Bernard Herrmann's music, instantly invoking that state of heightened dreaming that is cinema. Then the Paramount logo appears, in black and white, from which a huge V looms towards us, for all the world like a plunging scissors, becoming the centre of the word VistaVision (rarely can a brand name have seemed so ominous). Already, even before the titles have started, we're enveloped in the uneasy dream-mood of the film to come. This is no accident. As Bass explained, 'my initial thoughts about what a title can do was to set mood and the prime underlying core of the film's story, to express the story in some metaphorical way. I saw the title as a way of conditioning the audience, so that when the film actually began, viewers would already have an emotional resonance with it.' So the titles proper begin. The camera roams across a woman's face, from the pallor of her cheek to her pursed lips, from both eyes nervously looking askance to a close-up of one, liquid-dark eye. Feminine allure and mystery established we enter the spiraling world of that eye. 'Design is thinking made visual,' Bass declared, and somehow this sequence seems more than just visually striking. It's metaphor and hypnosis, endlessly mysterious and suggestive. When it ends our emotional resonance is well and truly primed for what's to come.

Labels:

great title sequences,

hitchcock,

saul bass,

Vertigo

Tuesday, September 14, 2010

Classic Scenes #18

The pleasure of this scene from Harvey (1950) isn't just the quoteable wisdom of the words but also the music of their delivery. While all the focus is rightly on Stewart's iconic Elwood P. Dowd, don't miss the plummy rhythms of Cecil Kellaway as psychiatrist Dr. Chumley, the way he uses those crisp consonants and rolling rs to run his words into each other, riding the internal rhymes of lines like 'this sister of yours is at the bottom of a conspiracy against you.'

But then there's that lovely, rueful 'Ohhh doctor' from Stewart and like one musician handing over to another, he begins his solo. Notice the run-over into the next sentence before 'she always called me Elwood', those softly echoing 'oh sos' and the warm emphasise of 'I recommend pleasant'. It's a masterclass of tone and rhythm and I never grow tired of hearing or seeing it.

But then there's that lovely, rueful 'Ohhh doctor' from Stewart and like one musician handing over to another, he begins his solo. Notice the run-over into the next sentence before 'she always called me Elwood', those softly echoing 'oh sos' and the warm emphasise of 'I recommend pleasant'. It's a masterclass of tone and rhythm and I never grow tired of hearing or seeing it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)